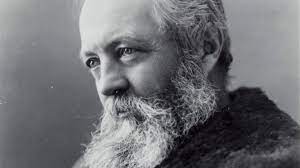

The 200th anniversary of the birth of Frederick Law Olmsted in 1822 has brought new attention to his groundbreaking work as a founder of landscape architecture. His parks are much praised for their beauty of design and their ability to bring much needed nature into the city. There is another central dynamic to his work that has received less attention. For Olmsted, beauty and nature were means to a higher goal: “A park is a work of art, designed to produce certain effects on the mind of men. There should be nothing in it, absolutely nothing – not a foot of surface nor a spear of grass – which does not represent study, design, a sagacious consideration and application of the known laws of cause and effect with reference to that end.”[1]

He defined those “certain effects on the mind” in a number of ways. His most ambitious goal was mental and physical healing. He set about the extraordinary task of providing relief from the mental suffering that afflicted the poor and working masses of New York. He noted that the rich had their manor estates for escape while the poor had nothing. As if that weren’t enough, he took on a second (perhaps more difficult) task which was to change the culture of public behavior in a city where dense, collective life was new to recent immigrants from the countryside. The idea that tens of thousands of people could coexist in a civil manner on 850 acres of open inner-city public land was a radical proposal hotly debated when the park was proposed.

How to go about designing public space to accomplish these goals was virtually unknown in the mid-19th century. Olmsted and his partner, Calvert Vaux, were making it up as they went along. Olmsted lamented this problem in a speech to the American Social Science Association: “The objective point of the practice of the art, the commodity which its practitioners undertake to supply, is a certain effect or class of effects on the human mind. There must be a psychological science of the subject and you may have reasonably expected me to teach you the outlines of this science. But I have to tell you that after much study and discussion I am satisfied with no presentation of it that has come to me. In the larger part, my practice has been based on the teachings of personal observations and experience that, certain conditions being attained, certain effects follow.”[2]

This paper will review Olmsted’s central design principles in light of modern psychological research. How do his assumptions stand up to modern research? Prior to his work in landscape, Olmsted had been a prolific writer. In addition to landmark works on life in the Antebellum South, he left us nine volumes of collected writings on landscape and city planning. This is the rich source from which we can understand his complex ideas about the dynamics of mental life in interaction with the land in its many forms.

An entire change of ideas and associations

Olmsted’s designs attempted to create rapid mental relief from the ills of city life. Park entrances would erase all suggestions of urban street life by creating a radical and complete change in the environment. “Scenery complete in itself, and that should offer, as soon as possible, to a visitor approaching from the city, an opportunity to enjoy an entire change of ideas and associations.” In design, this meant “all suggestions of streets, entrances or buildings being wholly done away with … no suggestion of immediate boundary.”[3]

The perimeter of the park was built to be a subtle barrier out of one’s awareness. Proposals for grand ornate entrances to the park were rejected. The paths into the park were sloped and densely planted to create a noise barrier.

To maintain the feeling you were in nature required that there be as few reminders of built city life as possible. Structures were kept to a minimum, often surrounded by plantings and hardscaping to obscure them. Natural wood timbers were the building material of choice for fences, railings and gazebos. A proposed suspension bridge was rejected because its wire and steel were too reminiscent of the built city.

The park was often seen as a desirable place for all manner of monuments, art works, entertainment venues such as a horse track and commercial businesses. Olmsted fought tirelessly against the majority of these proposals. “Objects before which people are called to a halt, and to utter mental exclamations of surprise and admiration, are often adapted to interrupt and prevent, or interfere with the process of indirect or unconscious recreation.”[4]

In the1960s researchers into the effects of movement through natural surroundings coined the term “evenly divided attention.” It is a state of mind entered into when there is enough freedom from built environmental cues. An exception was a beer garden in the center of the park. Olmsted pointed to the good behavior of those imbibing as an example of the civilizing effects of the park.

Psychology of the power of place

After a century of psychological research, we now understand that the mind does not churn out its constant train of thoughts within the confines of our head alone, although it seems to. The mind is embedded in our bodies, spending a large part of its energy monitoring our physical state. The body is in turn embedded in the environment, which is the source of the sensations and visual cues that trigger the content of thought. Shifts in inputs to the body and the senses all create mental effects often out of our awareness. “We have done all we could to ensure to every visitor an undisturbed enjoyment of their picturesque outline and of the whole train of associations they are naturally calculated to suggest.”[5]

The mental space to absorb these new associations has to compete with the time demanded by the cycle of ruminations about the past and anticipation of the future. Walking in a beautiful natural setting might not be enough to free the minds of park goers who are currently deeply stressed by their conditions of life. How to break into this cycle to bring the mindset of the park goer into the present was Olmsted’s central challenge.

His first lessons in landscape design that can change mental life were from his earlier travels in England. In Birkenhead Park in Liverpool he was first exposed to the naturalist style of park design in contrast to the formal row planting style more common in the day. He also began to see how nature can be “built up,” carved, and planted in such a way as to produce more robust mental effects than nature can alone.

“As a general rule, each element in their scenery is simple, natural to the soil and climate, and unobtrusive, and yet the passing observer is very strongly impressed with the manner in which views are successively opened before him through the innumerable combinations into which the individually modest elements constantly rearrange themselves; views which often possess every quality of complete and impressive landscape compositions. It is chiefly in this character that the park has the advantage for public purposes over any other type of recreation ground, whether wilder or more artificial. Other forms of natural scenery stir the observer to warmer admiration, but it is doubtful if any, and certain that none which under ordinary circumstances man can of set purposes induce nature to supply him, are equally soothing and refreshing; equally adapted to stimulate simple, natural, and wholesome tastes and fancies, and thus to draw the mind from absorption in the interest of an intensely artificial habit of life.”[6]

From these initial observations, Olmsted began his experiments with attention, imagination, memory, visual processing and illusions, spatial awareness, the mirroring of the feelings of others, social behavior, and mental health.

Holding attention to the present

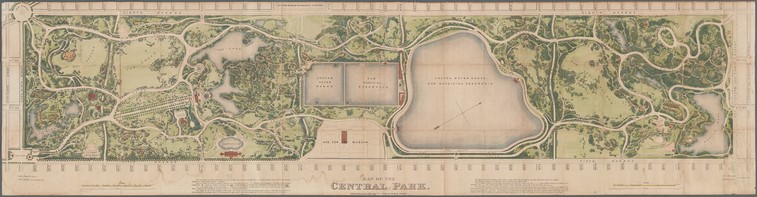

Looking at a map of Central Park you are struck by the curvilinear design of every path save the one straight line of the promenade. Understanding the power of the curved line was Olmsted and Vaux’s key insight into bringing park goers attention into the present time and place.

The curves tapped into what neuroscience now understands is the central dynamic that drives our attentional focus. As we move through the world, unconscious processes in our brains constantly predict what is about to happen, thereby guiding our movements and behaviors. If the coming experience meets our expectation, we tend to overlook what is before us. For example, if we are walking on a forest path and the ground remains flat, we predict that we don’t have to be aware of each footstep. However, if we step on a raised tree root, our prediction is proved to be incorrect and our attention wakes up to the present via a spike in the brain chemical dopamine. The error needs to be attended to and learned from. The power of the unpredicted to wake us to the present can be gratifying. The unpredicted is often what we enjoy in literature, theater, jokes, music, sports contests, travel, and even sex.

So how does this relate to path design for mental effects? When you are walking down a straight path, little is changing as you pass through it. You can predict what is coming from a distance. Information theorists say that there is little information in a straight line.

Research has shown that when a path becomes well known and unchanging, mental attention fades through the collapse of the firing of cells in place-holding areas of the brain. On a curved path, what is coming is constantly new. But more than curves are needed. The curved path must offer variation and unpredictability. Olmsted describes boring curves along an old rocky pathway in Central Park, “monotonous in its irregularity. … The eye is soon weary of the ceaseless repetition.”[7]

Safety in the park and the mind

With the senses bathed in natural scenery and undistracted, one has the chance to feel a transcendence into the environment. A feeling of safety is the essential gateway to this process. Olmsted described the effects of fear on behavior. “We want especially, the greatest possible contrast with the restraining and confining conditions of the town, those conditions which compel us to walk circumspectly, watchfully, jealously, which compel us to look closely upon others without sympathy.”[8]

Thanks to the work of Joseph LeDoux and others, we now understand how the brain detects and responds to danger. Sensing whether something out there is safe is a faster process in the brain than visually recognizing what it is. If your brain sees what it concludes to be a snake along the path, you will begin to flee or freeze before you fully visually recognize it and feel fear. The dangers of life in 19th century New York were many, leading to the potential for hypervigilance as the park is scanned for signs of pending danger.

Creating safety in such a huge space with, at times, tens of thousands of visitors was a challenge many thought impossible. Olmsted and Vaux’s design solution was to radically separate walking paths from carriage roads. Cross-park traffic was put seven feet below grade in four subterranean roads. (This won them the design competition.) Pathways separated pedestrians from carriage traffic in other parts of the park. Bridges, tunnels and overpasses were created to allow visitors to walk for great lengths without having to look right or left for oncoming traffic. The typical vigilance of city-street life could be put on hold.

Social psychology research has found that people tend to feel safer in the presence of others. Olmsted and Vaux designed promenades, meadows, plazas, picnic areas and playgrounds as gathering places to allow visitors to feel the safety of seeing and being seen. He took great pleasure in seeing the large meadows filled with thousands of picnic goers. “The most essential element of park scenery is turf in broad, unbroken fields, because in this the antithesis of the confined spaces of the town is most marked.”[9]

Another key to a sense of safety was the presence of a uniformed park police force. Knowing how to behave in a park was something new. Many people misbehaved simply because they were not aware of the effect of their actions on others. Olmsted assigned himself the chief of the park police force, wrote the rules for behavior in the park and trained the officers. A central tenet of his training was the power of their example rather than the threat of arrest. “The keeper can do little towards preventing misuse of the park, by arrests or threats or admonitions addressed personally to visitors. What is chiefly to be relied upon for keeping within necessary limits the thoughtless and slight misuse of the park is the impression on the minds of well intentioned visitors by the mere presence and manner of the peace keepers.”[10] This tenet resonates with debates over inner city police behavior today.

Playing with perception

Significant advances have been made in neuroscience to shed light on the way we perceive the world around us. A central finding is that perception is not simply the bringing in of sensations prompted by the surroundings. Our brains have to then make sense of it all in order to bring the inputs together. We are not seeing the world out there. We are seeing what our brains produce from those inputs.

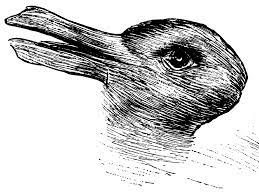

Bringing in the world through the senses is known as bottom-up processing while putting those sensations into coherent images is called top-down processing. Blending these two types of processing can create ambiguous images, depending on how the mix of past memories affects the ability to recognize what is attended to and the tone of the images presented. Perhaps you have seen this famous figure created to provoke ambiguity from your top-down processing.

Olmsted was constantly attempting to play with park visitors’ top-down processing by creating contrasts “for the influence of grace of topography like any other quality which influences our minds through the senses is enhanced by contrast.”[11] If he had an expanse that was too featureless, he would plant trees to create darkness and shadow. A second more advanced use of trees was to block sight lines. “The more important qualities of trees in landscape are those of termination and obscuration of view.”[12] If you obstruct a view, you stimulate the brain to creatively work, requiring it to consider what might be out there behind the obstacle rather than viewing passively and inattentively. Here is more of the idea of creating a sense of uncertainty, the unpredicted, “All limits should be so screened from view by trees that the imagination will be likely to assume no limit, but only acknowledge obscurity in whatever direction the eye may rove, … obscurity in some direction which presents a motive to wander.”[13]

Olmsted was explicit in his desire to create illusions. “No one looking into a closely-grown wood can be certain that at a short distance back there are not glades or streams, or that a more open disposition of trees does not prevail.”[14] When discussing the use of tropical plants, he spoke of an excited emotion that “rests upon a sense of the superabundant creative power, infinite resource, and liberality of Nature – the childish playfulness and profuse careless utterance of Nature.”[15]

A park designed as the eye sees

Research in optics has found that what we perceive clearly is concentrated in a central spot in the eye called the fovea. Here is found the highest concentration of color and light value receptors called rods and cones. We see clearly only that which falls on that spot. All that remains outside of it, our peripheral vision, is far less clear and more obscured.

Olmsted based his designs on this structure of the eye, which was far less understood in his day. “The term scenery is used … with regard to a field of vision in which there is either considerable complexity of light and shadow near the eye or obscurity of detail further away.”[16] He was following the natural tendency of vision to exaggerate the effects of his designs.

He used his understanding of the natural tendency of vision to further his quest to create new mental states through engaging visual processing more actively. “The quality of beauty in scenery lies largely in the blending in various degrees of various elements of color, texture and form and often more largely than in anything else in the obscurity and consequent mystery, giving play to fancy, of parts of the field of vision.”[17]

When Olmsted spent time in what is now Yosemite National Park,he noted that he preferred to look at the spectacular sites like Half Dome through shadow and fog.

A sense of enlarged freedom

Research has shown the negative effects of rows of straight buildings with no relief in sight. The mind associates walls and fences with confinement. Our capacity to imagine beyond this association is impaired. Grid pattern streets constantly restrain our view and ever taller buildings block the sky. We feel confined and, to a degree, enslaved to the maze.

“A man’s eyes cannot be as much occupied as they are in large cities by artificial things, or by natural things seen under obviously artificial conditions, with a harmful effect, first on his mental and nervous system and ultimately on his entire constitutional organization.”[18]

Olmsted had special spite for the popular cast iron picket fences of the day. Referring to iron rails in Hyde Park London, he said, “We should undertake nothing in the park which involves the treating of the public as prisoners or wild beasts. A great object of all that is done in a park, of all the art of a park is to influence the mind of men through their imagination, and the influence of iron hurdles can never be good.”[19]

In the brain, this anticipation of coming reward spikes dopamine, which in turn alerts attention and arousal. Olmsted powerfully created anticipated rewards by using large meadows terminated by dense shrubs in front of large trees to create an upward movement of the eye deep into space. It was in Prospect Park in Brooklyn that Olmsted had more land to work with to create this exaggeration of the sense of space. Removing several large ledges of rock created “an unbroken meadow which extends before the observer to a distance of nearly a thousand feet. Here is a suggestion of freedom and repose, which must in itself be refreshing and tranquilizing to the visitor coming from the hustle and bustle of the streets. But this is not all. … The observer cannot but hope for still greater space than is obvious before him.”[20]

He intentionally used the spacing of objects to further create the exaggerated effect of infinite distance. “A mile away at the end of the meadow an object was to be placed on a rock for the purpose of catching the eye, holding it in this direction. The imagination of the visitor is thus led instinctively to form the idea that a broad expanse is opening before him. As the visitor proceeds, this idea is strengthened and the hope which springs from it is to a considerable degree satisfied.”[21] The effect was exaggerated further by taking the park goer through a narrow path before entering a grand opening into a meadow. The brain is tuned to respond robustly to phase shifts in the visual field. At the entrance to the Long Meadow in Prospect Park, he achieved this effect most successfully.

Mind/body healing

It has long been noted that the stress of city life can have negative effects on physical health. Olmsted observed, “Civilized men, while they are gaining ground against certain acute forms of disease, are growing more and more subject to other and more insidious enemies to their health and happiness and against these the remedy and preemptive cannot be found in medicine or in athletic recreation but only in sunlight and such forms of gentle exercise as are calculated to equalize circulation and relieve the brain.”[22]

The effect of the mind on the body has been much researched in the past decades. Some studies have shown that a substantial percentage of visits to primary care doctors are for physical ailments with psychosomatic origins. Two aspects of physical health are particularly prone to benefit from time in a natural park. The first is to mitigate the hyperactivation of the stress response discussed earlier. The constant tension that comes from hypervigilance underlies a host of illnesses, from digestive disorders and heart attacks to obesity.

Stress generates a series of bodily responses to mobilize the fight or flight response to the danger (real or perceived). The first is an elevated heart rate. Chronic stress can create spikes in blood pressure and chronic hypertension. It spikes cascades of glucose to provide energy. Spikes in cortisol can reduce the body’s capacity to fight inflammation. Chronic secretion of glucose can produce obesity. One of the most damaging health effects of stress is the compromising of the immune system leaving the body more vulnerable to infectious disease.

These dynamics were little understood in the 19th century. Treatment was a matter of trial and error: Send people out of a stressful environment and see if they get better. Olmsted complained that at a time when the park was in decline in the mid-1870s, doctors stopped sending their patients to the park for fear of too much stress. Olmsted sometimes used the term “unbending” to describe the body’s opening to the new and invigorating environment he was creating.

The health problems related to stress are from chronic stress. The memories of the original stressors are mentally replayed over and over, long after the original stimulus, driving the continued over-activation of the stress response. This is why Olmsted was so preoccupied with giving the mind other things to hold its attention, providing pathways to shift the mindset entirely, relieving stress and opening the way to recovery.

Bessel van der Kolk is a leading researcher in the effects of trauma on the brain. His book “The Body Keeps The Score” is a run-away best seller. He discusses how severe trauma such as war can embody such fear that veterans no longer feel safe in their own body or in any environment. He prescribes practices that allow these veterans to reconnect with their bodies in the outside world. The idea is similar to Olmsted’s ideas of immersion in safe natural environments. Olmsted had intense exposure to the traumas of the Civil War when he headed the Sanitary Commission, setting up field hospitals for the Union Army. The Sanitary Commission later became the inspiration for the Red Cross.

Central Park was designed to serve New York as a public health facility with no medical staff, no appointments, no walls, no cost and no awareness you were in it. “The park is not simply a pleasure-ground … but a ground to which people may resort for recreation in certain ways and under certain circumstances which will be conducive to their better health. Physicians order certain classes of their patients to visit the park instead of prescribing medicine for them, because, they need first of all the insensible advantage which is gained in this way by thousands who visit it without this purpose definitely in view, but whose strength and powers of usefulness are thus increased, and whose lives thus prolonged, constitutes its chief value. … It must be remembered that a majority of all inhabitants of the city are women and children, sickly and aged or weakly, nervous and delicate persons and that the park is adapted to benefit none so much as those who have barely the courage, strength and nerve required to visit it.”[23]

Creating “communitive” people

Olmsted felt that the highly democratic and egalitarian nature of the park could even begin to “unbend” some of the debilitating effect of status anxiety, class shame, and racism against the tide of immigrants living in New York’s tenements at the time: “An opportunity for people to come together for the single purpose of enjoyment, unembarrassed by the limitations with which they are surrounded at home.”[24]

Olmsted was struggling with the larger question of what kind of citizens the young nation needed. “The tendency under given conditions to wanton destructiveness, to lawless selfishness, is always present, and was recognized at the beginning of the park as one of the great problems in its design and administrations.”[25]

Olmsted was a founder of the Nation magazine where the challenge of creating a new people free of greed, violence and slavery was discussed. What could this new society be called? On a visit to London he met with Karl Marx. They were both writing for New York newspapers: Olmsted for the New York Daily Times and Marx for the New York Daily Tribune. Marx was keen to hear Olmsted’s first-hand accounts of his observations of the slave economy of the South and its effects on culture. Olmsted later came up with the term “communitiveness” and set about to create the conditions for building a citizenry with more compassionate behavior within the microcosm of parks and urban design.

Social psychologists create experimental environments of social interactions to draw conclusions about human behavior. A rule of all research is that the robustness of the research findings is influenced by the number of subjects to rule out results caused by chance. The creation of Central Park became a massive social psychology experiment to test social behavior. The question was this: Can an environment be designed in a manner that shapes behavior in a positive direction? The number of subjects was in the millions.

While acting as the park superintendent, Olmsted wrote extensive reports on behavior in the park which summarized the results of his experiment; “No one who has closely observed the conduct of the people who visit the park can doubt that it exercises a distinctly harmonizing and refining influence upon the most unfortunate and most lawless classes of the city – an influence favorable to courtesy, self-control and temperance.”[26]

“When one is inclined to despair of the country, let him go to Central Park on a Saturday, and spend a few hours there looking at the people, not to those who come in gorgeous carriages, but at those who arrive on foot. We regret to say that the more brilliant the display of vehicles and toilettes, the more shameful is the display of bad manners. … The pedestrians always behave well.” [27]

A well designed park became a feedback loop where the environment uplifted the individual who in turn uplifted others by their example. Olmsted called this effect the “silent and unconscious influence.” He was anticipating recent findings that our brains contain what are called mirroring cells that can pick up the feelings of others and be affected by them.

Olmsted, like Marx and others, believed that the material conditions that people find themselves in have a predominant effect on their subjective life and behavior. He believed that people tend to adapt their conduct to the circumstances in which they find themselves, “and especially to be neat, cleanly, and nice where the objects about him are neat, cleanly, and nice.”[28] In the history of the park, the upkeep has gone through cycles of great care and then neglect with corresponding changes in park safety and care by its users.

Olmsted may be slipping into a bit of hyperbole in this description of the joys of feeling safe on a Sunday stroll in Central Park: “You will find a body of Christians coming together and with an evident glee in the prospect of coming together, all classes largely represented, with a common purpose, not at all intellectual, competitive with none, disposing to jealousy and spiritual or intellectual price toward none, each individual adding by his mere presence to the pleasure of all others, all helping to the greater happiness of each.. I have seen a hundred thousand thus congregated, and I assure you that though there have been not a few that seemed a little dazed, as if they did not quite understand it, and were, perhaps, a little ashamed of it.”[29]

Charm, grace, poetry and scenery

Olmsted struggled with the best language to describe this new state of mind that was in many ways ineffable, beyond language. “Landscape moves us in a manner more nearly analogous to the action of music than anything else. The attention is aroused and the mind occupied without purpose, without a continuation of the common process of relating the present action, thought or perception to some future end. … The enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it, tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it, thus through the influence of the mind over body, gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration of the whole system.”[30]

“This is simply a fact. If we want to go behind the fact – from the physician to the metaphysician – we must begin by reflecting that charm is something that acts, we know not how, to make us in some way different from what we should otherwise be, it acts otherwise than through our reason. “ [31]

When he said “we know not how,” he was clearly reflecting just how new these ideas were. He felt the effects of the park worked best when they are felt unconsciously. He was introduced to the ideas of unconscious influence by early 19th century writers who speculated on its effects on the mind. Its most famous advocate, Sigmund Freud, was two years old when the park was built. William James, the great pioneer of American psychology explored attention and the unconscious mind later in the 1890’s. Olmsted communicated with him, at one point sharing the content of his dreams for James to interpret.

He summarized the psychological power of scenery: “Scenery takes hold of the imagination chiefly to the degree that it tells stories or makes an impression of character. Thus scenery may be cheerful or gloomy, rude or refined, hospitable or forbidding, prosaic or romantic, sweet or bitter, stirring or reposeful, one or another of these or of scores of other descriptive terms long applied to it according to the manner in which it acts on the imagination.”[32]

Central Park was a trial run

After Central Park, Olmsted and his associates, including his two sons John and Frederick Jr., completed designs for more than 100 parks and recreation grounds. One of his last commissions was the design of the grounds of the Chicago World Columbian Exposition in 1893. The chief architects created massive structures of classical design known as the White City to hold the visitor in awe of industrial progress. Olmsted pushed for the building of a midway amusement area complete with a large pond with electric pleasure boats where people could play and be gay. His focus on the centrality of positive mental effects in design had not faded.

What Olmsted accomplished in his career was a paradigm shift in how landscape design could be approached. Prior to his work (and, to an extent, still today) landscape and city designs were based on utility and beauty. He created a design discipline centered on the psychological well-being in the lives of those who strolled the parks.

In the end

It is a cruel irony that a man who had spent his life in the business of stress relief for masses of people suffered extraordinary stress in his own life. Many of his commissions involved substantial battles over aspects of design and cost. He was prone to anxiety and depression. Sprints of intense work, sometimes 20 hours a day, were followed by collapses into exhaustion and melancholy that could incapacitate him for weeks. Due to advancing dementia near the end of his life, he was committed to McLean Hospital where, years before, he had designed the grounds. So the story goes, as he was wheeled in, he grumbled about what a bad job they had done in following his designs, “Confound them!”

A very special role in chronicling the works and ideas of Olmsted was played by Charles E. Beveridge. He edited the collected works of Olmsted and was the author of numerous books on Olmsted parks and design ideas. He was the first to significantly explore the psychological theories that guided Olmsted’s work.

John Olmsted, MA, MEd. Retired teacher of psychology and neuroscience and sometime artist in Portland, Oregon. He is a member of the family that founded Hartford, Connecticut.

Bibliography

Beveridge, Charles E. & Hoffman, Caroline F., The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted Supplementary Series, Vol. I, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press,1997

Beveridge, Charles E., Hoffman, Caroline F. & Hawkins, Kenneth, The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. VII, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007

Beveridge, Charles E. & Schuyler, David, The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. III, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983

Beveridge, Charles E. & Rocheleau, Paul, Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing The American Landscape, New York, Universe Publishing, 1995

Fein, Albert, Frederick Law Olmsted and the American Environmental Tradition, New York, George Braziller, 1972

Kaplan, Rachel. & Kaplan, Stephen, The Experience of Nature, A Psychological Perspective, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989

Kelly, Bruce, Guillet, Gail T., Hern, Mary Ellen W. & Simpson, Jeffrey, Art of The Olmsted Landscape, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1981

LeDoux, Joseph E., The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life, New York, Simon and Schuster, 1996

Martin, Justin, Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted, Cambridge, Da Capo Press, 2011

Olmsted, Frederick Law, Forty Years of Landscape Architecture: Central Park, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1928

Roper, Laura W., FLO A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973

Rybczynski, Witold, A Clearing In The Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the 19th Century, New York, Scribner, 1999

Sapolsky, Robert M., Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, New York, Henry Holt & Co., 2004

The Cultural Landscape Foundation, Birnbaum, Charles, Tasse-Winter, Dena & Levee, Arleyn, Experiencing Olmsted: The Enduring Legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted’s North American Landscapes, Portland, Timber Press 2022

van der Kolk, Bessel , The Body Keeps The Score: Brain, MInd and Body in the Healing of Trauma, New York, Penguin Publishing, 2015

[1] Charles Beveridge and Carolyn Hoffman, eds., Kenneth Hawkins, assoc. ed., The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, (Supplementary series Vol. 1, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 1997) 155

[2] Charles Beveridge and Paul Rocheleau, Frederick Law Olmsted – Designing the American Landscape (New York, Universe Publishing, 1998) 35

[3] Charles Beveridge, ed. The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted Vol. 3 (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 1983) 184

[4] Beveridge and Rocheleau, op. cit. 31

[8] Beveridge, et al, op. cit. 189

[9] Beveridge, et al, op. cit. 311

[11] Ibid 154

[12] Ibid

[13] Ibid

[14] Beveridge, op. cit. 185

[15] Ibid

[16] Beveridge and Rocheleau, op cit. 37

[17] Ibid

[18] Beveridge, et al, op. cit. 471

[19] Ibid 190

[20] Beveridge, op. cit. 183

[21] Ibid

[22] Ibid 10

[24] Beveridge 87

[25] Ibid 289

[26] Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and Theodora Kimball, Forty Years of Landscape Architecture: Central Park (Cambridge Mass., MIT Press, 1973) 193

[27] Beveridge, et al, op. cit. 198

[28] Ibid 390

[29] Beveridge and Rocheleau, op. cit. 47

[30] Beveridge, et al, op. cit. 366

[31] Ibid

[32] Beveridge and Rocheleau, op. cit. 33