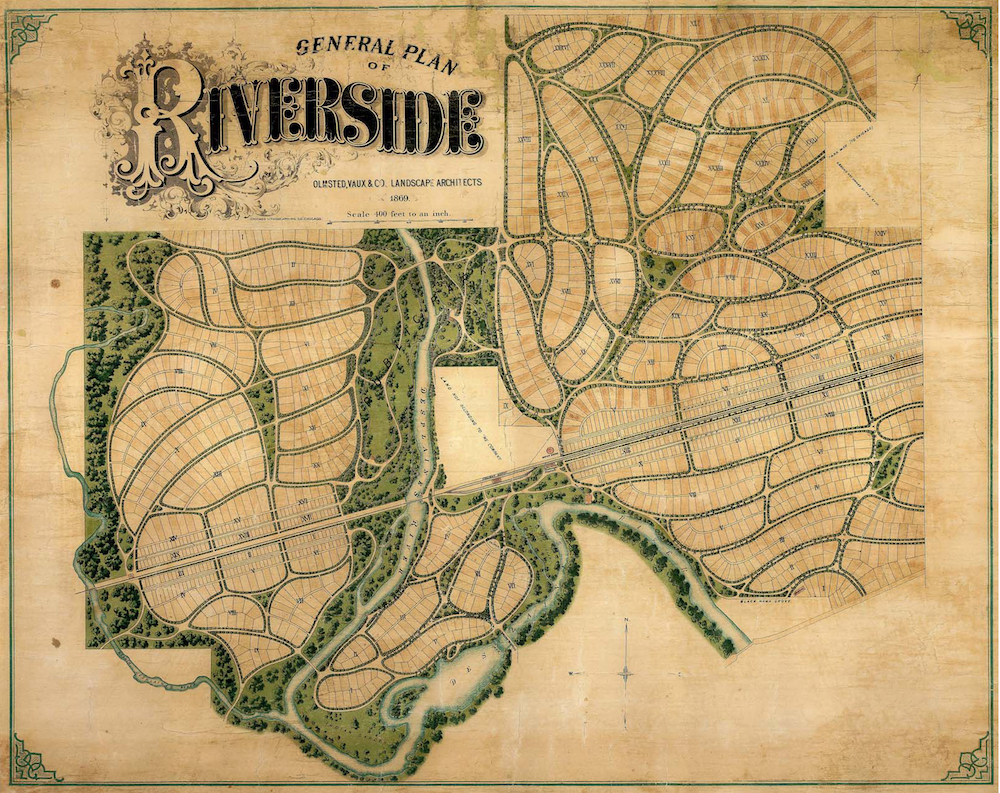

Sudbrook, a suburban community near Baltimore designed in 1889 by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., is smaller and less well-known than the 1,600 acre Riverside, Illinois (1869) and the 1,400 acre Druid Hills, Georgia (1893), but equally important to his legacy of early suburban design.

Sudbrook’s connection with Olmsted dates from 1876, when James Howard McHenry, descended from a distinguished Maryland family, contacted Olmsted to design a suburban village on McHenry’s 850-acre “Sudbrook” estate. They corresponded at intervals through 1878, but McHenry’s long-standing interest in developing a suburban community on his estate did not reach fulfillment before his death in September 1888.

Within months of McHenry’s death, the Sudbrook Land Company (formed by Boston and Philadelphia investors, with Baltimorean Hugh Bond as President) purchased 204 acres from the McHenry estate, resumed correspondence with Olmsted and his stepson, John Charles Olmsted, and by August 1889, had received Olmsted’s completed plan for “Sudbrook.”

Olmsted’s design for Sudbrook, exceptional for its time, remains a work of art. In an age of arrow-straight streets, Olmsted’s roads of continuous curvature were so novel that the Sudbrook Company initially could not find a surveyor to stake them out.

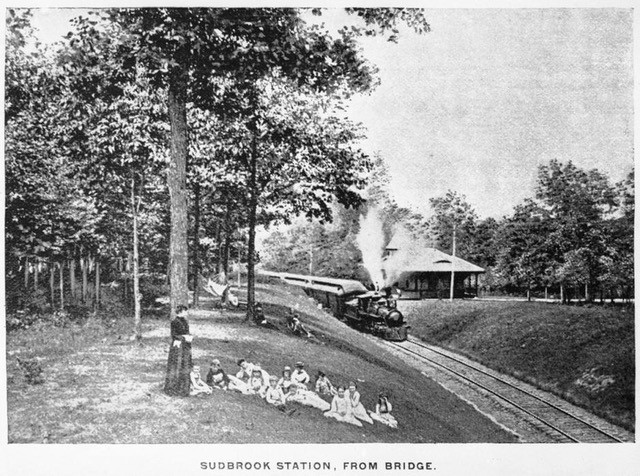

Between August 1889 and May 1890, the Sudbrook Company turned Olmsted’s Plan into what it hoped would be a permanent suburban village, constructing a train station, entranceway bridge, an Inn and nine initial “cottages” to entice purchasers.

A one-mile approach road into Sudbrook led carriages off a main road into Pikesville around several curves to a narrow entranceway bridge, after which the constricted vista opened with five gracefully curving roads branching out like streamers through the community. Nestled between the entranceway roads were greenspaces and “triangles,” providing picturesque areas for visitors and informal, shaded gathering spots for residents.

While preserving many existing native trees, Olmsted added more along roadways at 50-60 foot intervals, “so that they will come opposite each other on a curved street.” He separated visually distracting modes of transportation by placing the bridge and primary entranceway high above the rail line and using slightly sunken roadways to keep them from impeding the view.

Olmsted drew up sixteen deed restrictions that he considered as much “a part of a plan for a suburb . . . as certain lines on paper.” They governed lot size (generally about an acre), setbacks (40-feet) and style (distinctly rural); excluded commercial activities; required acceptable sanitation practices; and limited cows and horses (pigs were prohibited). Olmsted also included smaller lots for those with less financial means, a practice uncommon at the time.

Baltimoreans loved Sudbrook (renamed ‘Sudbrook Park’ before it opened in Spring 1890), but they were reluctant to adopt year-round suburban living until after 1910. Sudbrook’s distance from the city, erratic train service, and the deed restriction that required a dwelling house to be constructed within 2 years of lot purchase, all worked to dampen sales when suburban living was still a novel idea. A second wave of development from 1939 – 1954, with smaller-lot brick Neo-Colonials along roads that tried to emulate the original plan, completed the community’s development.

Sudbrook has weathered time, major public works’ threats and many changes since it was originally designed as an innovative suburban village by America’s first and foremost landscape architect. That it has been a vibrant, cohesive community and “respite for the spirit” for 133 years is a tribute to Olmsted’s genius, vision and design.

Melanie Anson is author of Olmsted’s Sudbrook: The Making of a Community.