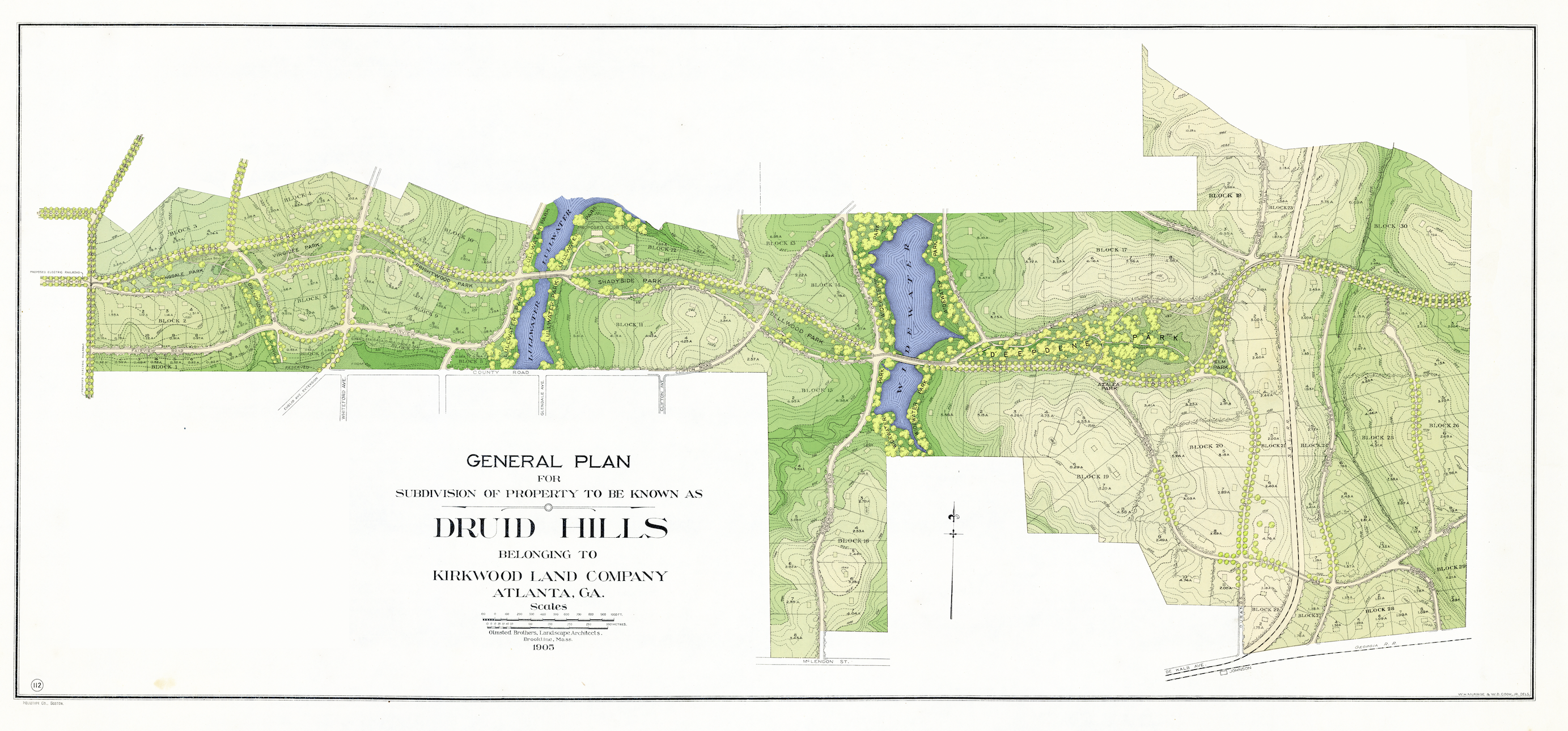

Druid Hills, now one of Atlanta’s historic in-town neighborhoods, is Frederick Law Olmsted’s “last suburb.” Three men made Druid Hills happen. Joel Hurt, one of Atlanta’s trolley kings and an enlightened developer, brought Mr. Olmsted to Atlanta in 1890 to design an “ideal residential suburb.” Working at the time at the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, Frederick Law Olmsted traveled by train, streetcar, and then on horseback to see the 1400 acres of woodland and scrub farmland that Hurt had amassed. By 1893, Hurt had a conceptual plan. A linear park and parkway formed the centerpiece of the design for a residential community of spacious lots with generous setbacks along curvilinear streets. A trolley running on a single track along the edge of the park connected the subdivision to the city. It took another prominent Atlanta businessman to launch the development of the plan after Hurt sold his Druid Hills project to the Druid Hills Corporation headed by Coca-Cola magnate Asa Candler for a record half-million dollars. By this time, Olmsted had retired (1895) and his sons were carrying on the firm as the Olmsted Brothers. John Charles Olmsted was the brother on the ground in Atlanta overseeing the project, laying out the parkway and park segments and drawing up planting plans, and producing the famous 1905 Plan.

Lots began to be sold and houses were built after the 1908 sale. Prominent citizens, mostly businessmen and professionals and their families moved to the new “suburb,” several miles from Inman Park, Atlanta’s “first suburb” developed by Hurt in the 1880s where he built his own home and ran a trolley line to his office downtown. All of Asa Candler’s children built homes in Druid Hills as did their father. A number of homes were “built by Coca-Cola” including two houses said to be wedding presents. Seven of Atlanta’s most prominent architects of the early 20th century built their own homes here in addition to designing homes for clients. Characterized by a range of architectural styles, particularly Revival styles of Classical (the 1893 Columbian Exposition’s influence) and Colonial and Mediterranean, Druid Hills offers an eclectic array sometimes within the design of a single house. What is consistent is the scale, mass, and proportion of the homes and their relation to the street and to each other. It is the spatial relations established by the Olmsted plan/design that are the focus of the protection afforded by both the City of Atlanta and DeKalb County historic preservation ordinances sought and gained by the Druid Hills Civic Association beginning in the 1970s with the National Register listing of the Druid Hills Parks & Parkways followed quickly by the entire “suburb.”

While changes occurred before World War II like smaller lots in the northern section where Emory University established an Atlanta campus with the gift of land and a (famous) million dollar check from Asa Candler and the development of smaller subdivisions flowing from the Olmsted design, more dramatic change occurred in the years following the war. The trolley disappeared, the spacious parkway was turned into a four-lane state highway, the mansions along the main parkway became too much for single-family use and a major threat to the very existence of Druid Hills arrived in the form of a road that would link the city to its burgeoning eastern suburbs. The first iteration of this threat in the 1970s was squelched by the then-governor. The second iteration – re-surfacing in the 1980s as a “parkway” (with Interstate highway specifications) having strong local governmental support– put Druid Hills and almost all the in-town neighborhoods between Druid Hills and downtown into a protracted decade-long fight, complete with protests, arrests, court cases, and a change of mayors. The Olmsted Parks Society was formed with its initial focus on raising awareness of the man who designed Druid Hills and what a valuable place Druid Hills was. The Road would have meant the beginning of the end, cutting through the middle of the linear park and emptying onto the parkway. NAOP was a lifeline, a national voice for what being part of the Olmsted legacy meant. The National Trust stepped up as well. The election of a new mayor and subsequent successful mediation ended The Road Fight. Then, in preparation for the 1996 Olympics, the parkway became one of the Garden Club of Georgia’s “Pathways of Gold” paving the way for a master plan for restoration and rehabilitation of the Druid Hills linear park to be called Olmsted Linear Park and looked after by a newly-created Olmsted Linear Park Alliance (OLPA).

Both the Druid Hills Civic Association and OLPA are members of NAOP’s Olmsted Network. Both are supporting the Proclamation joining Riverside (Illinois) and Druid Hills – Frederick Law Olmsted’s “first and last suburbs” – in a mutual effort of education and understanding.

To learn more about the Olmsted Linear Park Alliance, click here.