A new book highlights part of Frederick Law Olmsted’s legacy in Milwaukee. Riverside Park was one of three parks he designed there from 1892 till 1895. The park is now incorporated within the Milwaukee River Greenway, which comprises 878 acres of riverfront parks and other conserved land. The eight-mile-long Greenway is accessible through recreational trails and includes wetlands, woodlands, and deep river valley.

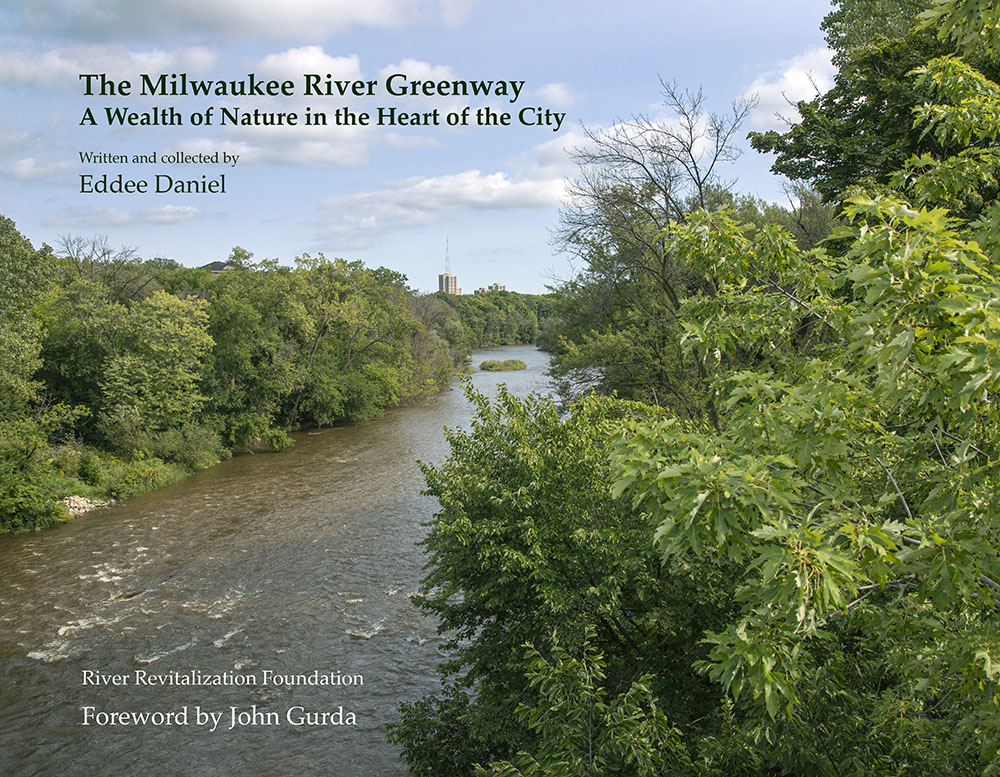

Milwaukee River Greenway: A Wealth of Nature in the Heart of the City is published by River Revitalization Foundation (RRF), an urban land trust that has led the effort to connect and revitalize land bordering the city’s rivers. The Milwaukee River Greenway extends from north of downtown Milwaukee through the city and two northeastern suburbs.

The book was published as part of a 15th-anniversary celebration of the Greenway. (See more: https://www.riverrevitalizationfoundation.org/milwaukee-river-greenway/). Eddee Daniel is the 230-page book’s author, editor and photographer. (Learn more: https://awealthofnature.org/). It includes a compelling collection of photographs, essays, and personal stories of kayakers and hikers, anglers and birders, dog-walkers and suburban picnickers. These contributors “extol its virtues, lament its travails, honor its resilience, and express gratitude for the hope it engenders,” Daniel wrote.

When Daniel invited me to write a chapter about the origins of Riverside Park, I jumped at the opportunity to explore in more depth this aspect of Olmsted’s Milwaukee legacy. I had written an article in 2017 for Milwaukee Magazine titled “Olmsted Deserves Recognition in Milwaukee“, and I frequently give tours of Olmsted parks here. The book’s timing is also fortuitous as groups throughout Milwaukee and Wisconsin are gearing up to celebrate Olmsted 200.

Olmsted worked in Milwaukee during the last phase of his prolific career. He was enlisted for these projects while he was designing landscapes for the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, which opened in 1893. Milwaukee’s nascent city park commission hired Olmsted to help select seven sites for parks and to design three of them. He master-planned what he named Milwaukee’s “Grand Necklace of Parks”: Lake, Riverside, and Washington parks and East Newberry Boulevard, which gracefully connects the first two.

Olmsted envisioned these parks as a linked “system” with varying qualities and experiences, as he had first done in Buffalo with architect Calvert Vaux, starting in 1868. Milwaukee parks proponent Charles B. Whitnall built upon Olmsted’s ideas about complementary—and often interconnected—metropolitan parks when he conceived in 1923 a countywide park and parkway system incorporating its waterways. That plan was largely implemented during his decades-long tenure as a park commissioner, in collaboration with landscape architect Alfred L. Boerner.

Naturalistic Landscape Design

Each park Olmsted designed for Milwaukee accentuated existing natural resources, such as the Milwaukee River, and existing terrain, such as bluffs, hills, woods, and ravines. That gave them distinctive landscape character while emphasizing naturalistic, rather than formal, structure.

River Park, as it was then called, faced a daunting design challenge: being bisected by the Chicago and North Western Railway. Olmsted’s design included a carriage drive from Newberry Boulevard through a naturally occurring ravine, via a massive limestone-block tunnel down to the river. From there it wound back uphill to a parallel street. Although the tunnel was eventually filled in, the stone structure remains visible in the park’s woodland.

Paul Daniel Marriott, a landscape architecture professor and board member of the National Association for Olmsted Parks, found the changes within Riverside Park intriguing during a recent visit. He observed, “It is clear that the rail line through Milwaukee’s Riverside Park would not have been an ideal situation for Olmsted—a dirty, noisy depression, belching thick black smoke during regularly scheduled interruptions to pastoral retreat. Nevertheless, as with so many of Olmsted’s projects, he made compromises and accommodations to reflect the built realities of the site.” Marriott added, “Today, I am confident that Olmsted would look back on the rail line as one of the greatest opportunities afforded the park,” as it later became part of a metropolitan recreational trail. “Fortunately, Milwaukee had the vision to apply the great landscape architect’s park plan to 21st-century opportunities.”

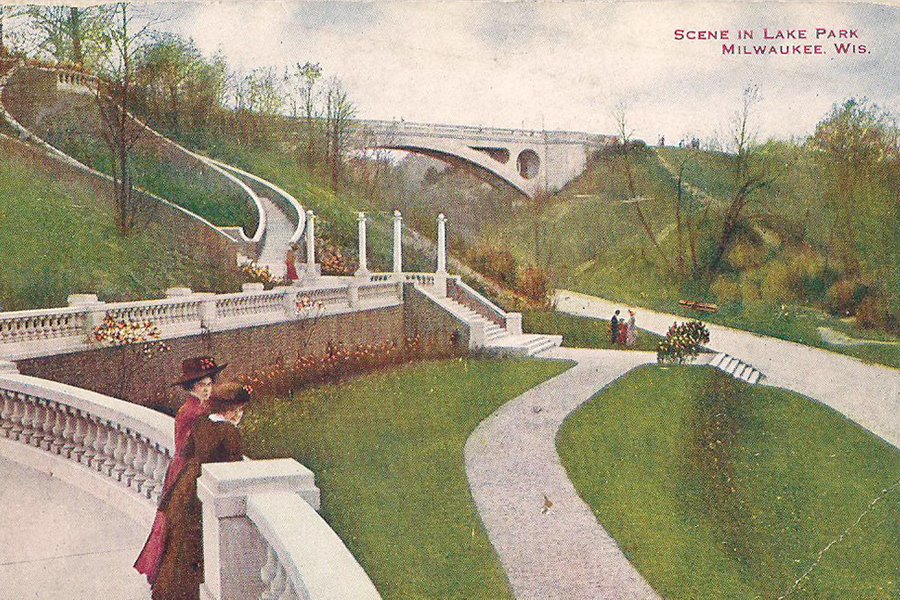

Olmsted’s designs of these linked green spaces enabled strollers and carriage riders to promenade between the Milwaukee River and Lake Michigan. They reflected a key Olmstedian design principle: to create a well-orchestrated sequence—with “passages of scenery” for visitors to enjoy. He also successfully urged city officials to build streetcar stops near these parks, to ensure easy and equitable access for all.

Olmsted planned for water-based activities as the focus of recreation in River Park: swimming, boating, ice skating, and gathering on the riverbanks. Of course, that was before rampant pollution resulted in people turning away from the Milwaukee River for many decades.

Olmsted and the Greenway Concept

Since Olmsted designed, with Calvert Vaux, Prospect Park starting in 1866, he had been a fierce advocate for “park-ways”—green strips of parkland (which often, but not always, included a pleasure drive) to connect larger parks within a system. Whether envisioned by Olmsted or Whitnall, Milwaukee’s extensive parkways are legacies of these ideas—as is the entire Milwaukee River Greenway.

“Arguably if any single person invented the idea of greenways, it was he,” Charles E. Little wrote of Olmsted in Greenways for America. In this book, Charles E. Beveridge, editor of the Frederick Law Olmsted Papers, traces what was essentially a greenway in Olmsted’s design for the College of California in Berkeley–back in 1865. I learned about the Berkeley greenway, although it was not specifically called that, while researching my chapter for this book. I was fascinated that it actually predated Olmsted’s “parkway” concept.

So how are greenways and parkways related? Functionally, both focus on linking green spaces. Ecologically, they often support what we today call “environmental corridors.” Parkways generally, but not always, have included a roadway. Boston’s “Emerald Necklace” of linked parks along the Muddy River is perhaps Olmsted’s most fully realized example of a greenway, according to Beveridge.

Much of the Milwaukee River Greenway project focuses on restoring areas along the river that had become degraded over time, whether through pollution, industrial uses, dams, or other human interventions. The Greenway project was initiated through grass-roots efforts and is taking shape through a community-based master plan for preservation, revitalization, management, and improved public access and recreation. A coalition comprising governmental agencies and nonprofit organizations, including Milwaukee Riverkeeper, the Urban Ecology Center, and RFF, also involves many volunteers.

Olmsted’s visionary ideas and design contributions—in Milwaukee and beyond—remain relevant and inspiring today. They can inform contemporary planning, problem-solving, and aesthetic decision-making, as is evident within the Milwaukee River Greenway. An interwoven whole can indeed become greater than the sum of its parts.

How to purchase:

Milwaukee River Greenway: A Wealth of Nature in the Heart of the City can be ordered from here. It is also available in Milwaukee at Woodland Pattern Book Center, The Little Read Book, and the River Revitalization Foundation.

ISBN: 978-1-09839-041-9, published by River Revitalization Foundation. Virginia Small is an independent journalist and researcher into landscape histories. Milwaukee’s Lake Park remains one of her favorite places. “I often thought of it as a touchstone during decades living away from my hometown,” she said. “I am now grateful to live two blocks away from this Olmsted legacy park. I enjoy it in all seasons and all types of weather. I especially treasured sunrises and frequent respite there during the pandemic.”