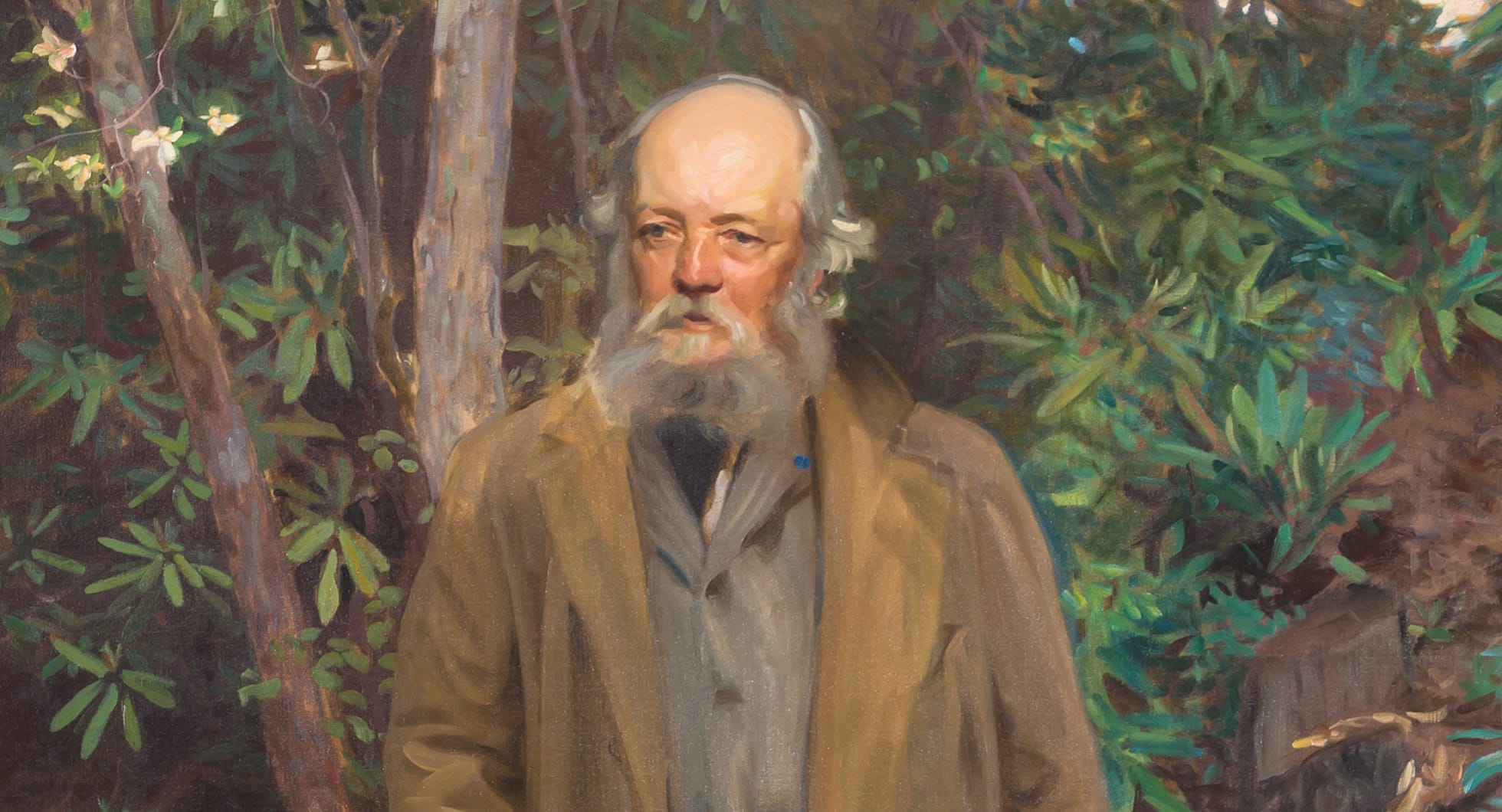

The root of all my good work is an early respect for, regard and enjoyment of scenery … and extraordinary opportunities for cultivating susceptibility to the power of scenery.”

Frederick Law Olmsted to Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, 1893

In 1850, Olmsted took a six-month walking tour that was to prove life-changing. He paid a visit to Liverpool’s Birkenhead Park, a rare public park, open to all. There, Olmsted concluded that park access should be a right of all Americans. “I was ready to admit,” he wrote, “that in democratic America there was nothing to be thought of as comparable to this People’s Garden.”

A Voice for Change: Reporting for The New York Daily Times

Olmsted was commissioned by the New York Daily Times in 1852 to visit the South and examine the system of slavery. Most Northerners had little understanding of the slavery system or the South in general. The Times wanted a traveling correspondent who would “confine his statements to matters that he observed personally.”

Traveling under cover, and with the same gusto he had as a child, Olmsted took boats down the Mississippi, rode horseback and walked the countryside, visiting with strangers all the way to west Texas. Between 1856 and 1860, he published three volumes of his accounts and social analyses of these travels. During this period, he used his literary skills to oppose the westward expansion of slavery and to argue for the abolition of slavery by the Southern states.

Bow Bridge in Central Park. The bridge was designed by Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould and completed in 1862.

Preserving America’s Scenic Spaces

In 1863, Olmsted moved to California to manage the Mariposa Estate and gold mines, just miles from Yosemite Valley. There he experienced a landscape quite different from the Connecticut River Valley of his youth — and one threatened by private commercial interests.

The federal government had just granted Yosemite to California, and Olmsted was asked to head a commission overseeing the Yosemite reservation. In August 1865, he released a Report on Yosemite to members of the Commission.

It is the “main duty of government,” he wrote, to “provide means of protection for all its citizens in the pursuit of happiness” against the obstacles posed by the “selfishness of individuals or combinations of individuals.”

It would be many years before the birth of the national park system, but Olmsted’s report laid the foundation. In 1916, Olmsted’s son helped draft legislation creating the national parks. Olmsted’s thinking in Yosemite also informed his later international campaign to preserve Niagara Falls.

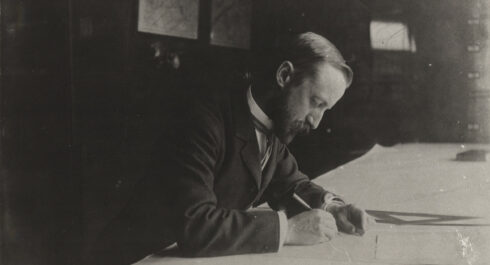

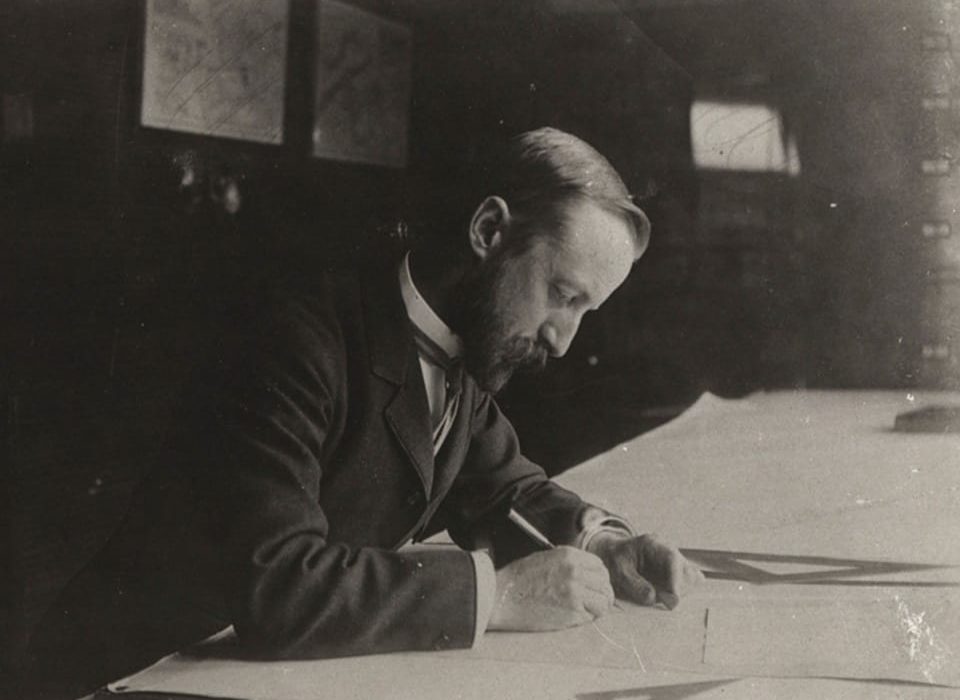

Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.

John Charles Olmsted

(L to r): James Frederick Dawson, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and Percival Gallagher

A New Generation of Olmsteds

Olmsted retired in 1895, but his sons, John Charles and Frederick Jr., carried on, and the Olmsted firm was a functioning landscape practice for over 100 years with commissions for about 6,000 landscapes across North America. (Frederick Jr. was christened Henry Perkins and renamed by his father when he was about eight. He often dropped Jr. in his correspondence so it can be difficult to determine the true identity of Olmsted’s writing.)

The firm was almost singlehandedly responsible for developing the profession of landscape architecture and training generations of professionals, many of whom created their own firms, such as Charles Eliot, Warren Manning and William Lyman Phillips.

John Charles was a founding member of the American Society of Landscape Architects and Frederick Jr. established Harvard’s Landscape Design Program. Today, the Landscape Architecture Foundation honors the Olmsted heritage by selecting annual Olmsted Scholars who are budding stars in the field.

Fairsted, which served as both the home and workplace for Frederick Law Olmsted, is now a part of the National Park Service.