Life

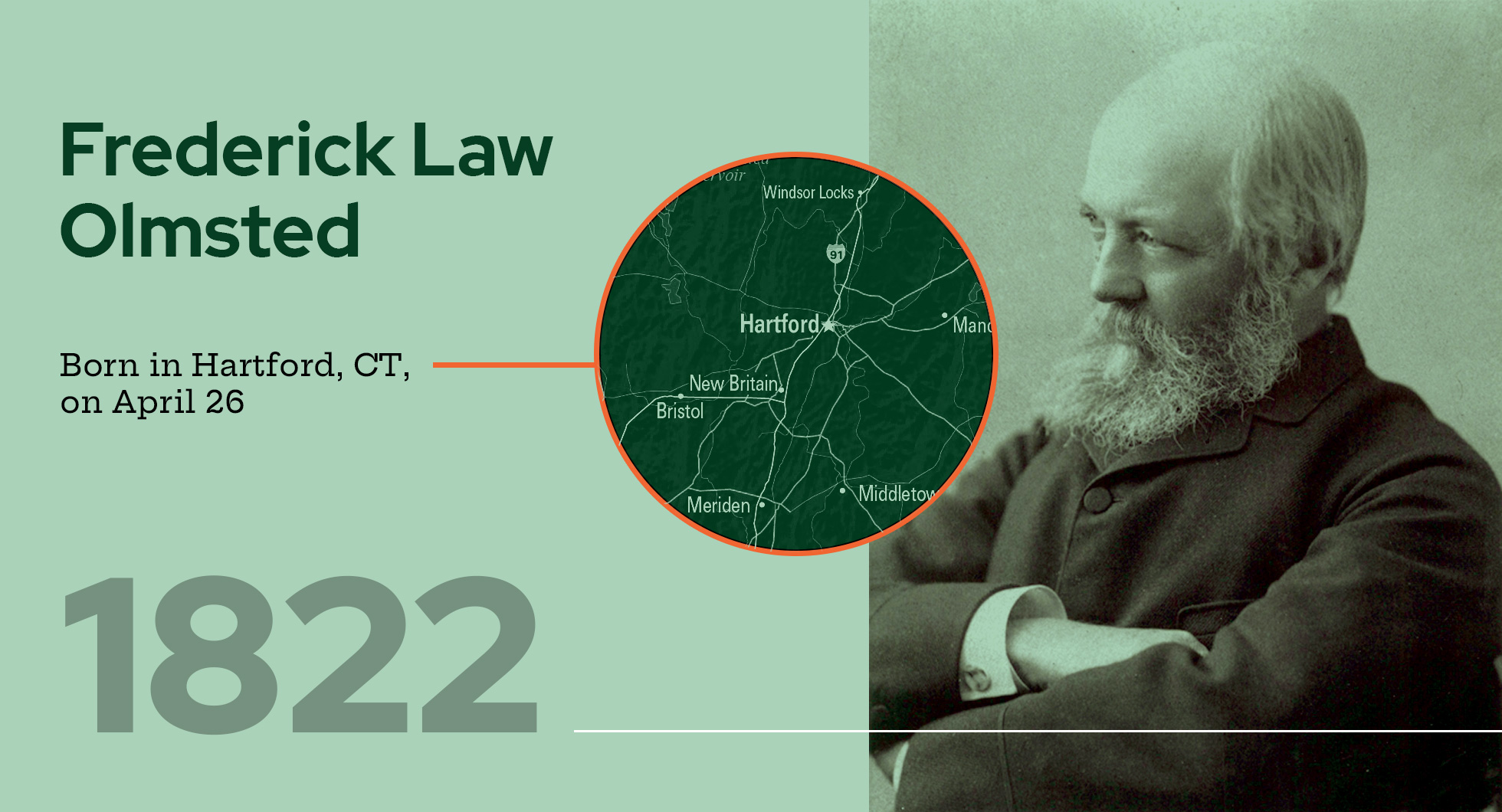

Frederick Law Olmsted

Landscape architect, author, conservationist and public servant.

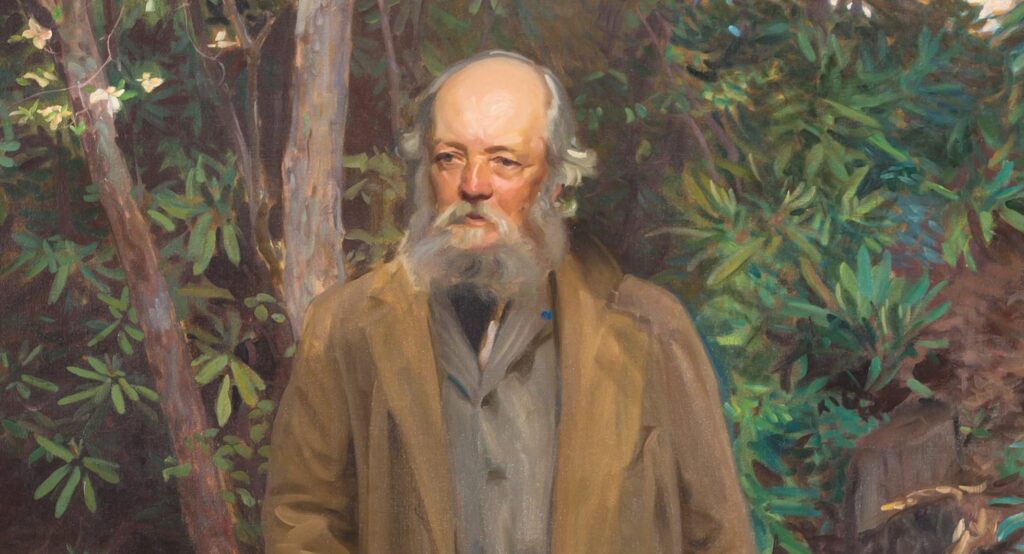

Frederick Law Olmsted (detail) by John Singer Sargent. Used with permission from The Biltmore Company, Asheville, North Carolina.

Early Life

Frederick Law Olmsted was born in Hartford, CT, where his family had lived for eight generations. His father, a successful dry-goods merchant, loved scenery and took Olmsted on regular trips through the countryside. Early on, Olmsted developed a great love for travel.

“The root of all my good work is an early respect for, regard and enjoyment of scenery… and extraordinary opportunities for cultivating susceptibility to the power of scenery.”

— Frederick Law Olmsted to Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer (1893)

Olmsted showed little love, however, for formal education. He was schooled largely by ministers and briefly attended Yale. But sickness caused him to withdraw after his first semester. For the next 20 years he “gathered experiences,” which helped shape his landscape design: a year-long voyage in the China Trade, farming on Staten Island, reporting for the New York Daily Times, and serving as partner in a publishing firm and managing editor of a literary and political journal.

In 1850, Olmsted took a six-month walking tour that was to prove lifechanging. He paid a visit to Liverpool’s Birkenhead Park, a rare public park, open to all. There, Olmsted concluded that park access should be a right of all Americans. “I was struck,” he wrote, “that in democratic America there was nothing to be thought of as comparable to this People’s Garden.”

A Voice for Change: Reporting for The New York Daily Times

Olmsted was commissioned by the New York Daily Times in 1852 to visit the South and examine the system of slavery. Most Northerners had little understanding of the slavery system or the South in general. The Times wanted a traveling correspondent who would “confine his statements to matters that he observed personally.”

Traveling under cover, and with the same gusto he had as a child, Olmsted took boats down the Mississippi, rode horseback and walked the countryside, visiting with many strangers all the way to west Texas. Between 1856 and 1860, he published three volumes of travel accounts and social analyses of these travels. During this period, he used his literary skills to oppose the westward expansion of slavery and to argue for the abolition of slavery by the Southern states.

The late author Tony Horwitz retraced Olmsted’s footsteps in Spying on the South. Learn more here

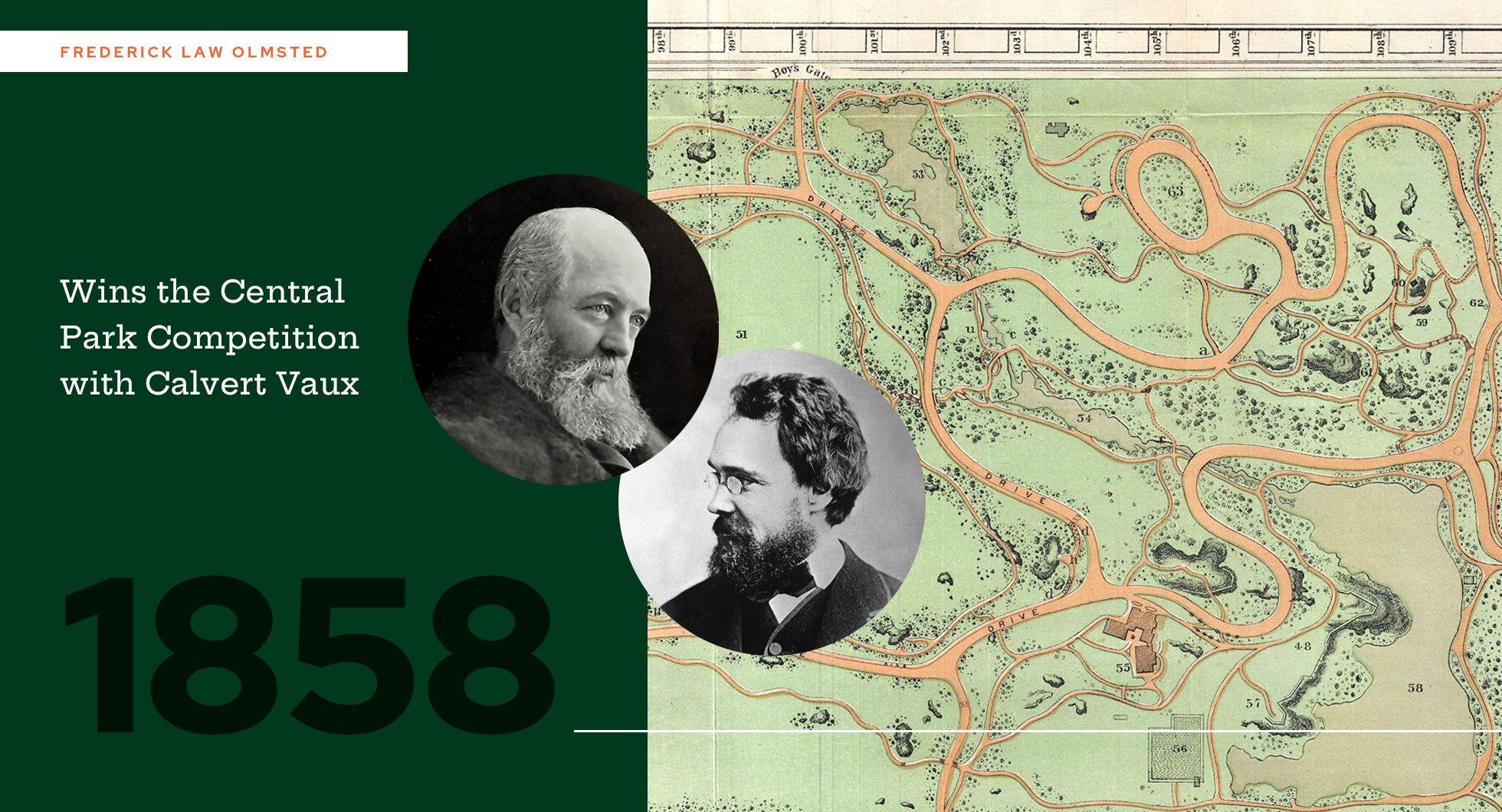

The Birth of Central Park

Thanks to powerful connections made through his literary pursuits, Olmsted secured the position of superintendent of Central Park in 1857. A few months later, Calvert Vaux, a rising young architect from England, asked Olmsted to join him in preparing an entry for the Central Park design competition.

Working against the looming deadline, Olmsted and Vaux created the Greensward Plan and beat 32 competitors. They designed unique transverse roads, sinking them so that travel through the park would not distract from the landscape experience or be dangerous. They created a path system that subtly directed people’s movements. In so many ways, Central Park proved a testing ground for design principles incorporated into his later work.

In a massive public works project, 3,000 workers moved “nearly 50 million cubic yards of stone, earth and topsoil, built 36 bridges and arches, and constructed 11 overpasses…. They also planted 500,000 trees, shrubs and vines.”

Central Park took 15 years to complete. Learn more here.

The U.S. Sanitary Commission

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Olmsted left Central Park to take a new position in Washington, D.C., becoming the first Executive Secretary of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, the forerunner of the American Red Cross. Olmsted was tapped to apply the same organizational skills he had honed in the building of Central Park to the Union Army, which was beset with challenges. He was charged with overseeing camp sanitation and creating a national system of medical supplies for the troops.

Assisted by volunteers, Olmsted implemented an array of health practices, including exercise and good nutrition. At the same time, he invented medical ships — retrofitting military boats in record time to serve as floating hospitals. Thanks to the practices Olmsted put in place, thousands of lives were saved, and the experience proved critical in strengthening Olmsted’s understanding of the importance of sanitation and sanitary engineering — essential tenets in his landscape designs, both before and after the war.

Preserving America’s Scenic Spaces

In 1863, Olmsted moved to California to manage the Mariposa Estate and gold mines, just miles from Yosemite Valley. There he experienced a landscape quite different from the Connecticut River Valley of his youth — and one threatened by private commercial interests. The federal government had just granted Yosemite to California, and Olmsted was asked to head a commission overseeing the Yosemite reservation. In August 1865, he released a Report on Yosemite to members of the Commission. It is the “main duty of government,” he wrote, to “provide means of protection for all its citizens in the pursuit of happiness” against the obstacles posed by the “selfishness of individuals or combinations of individuals.” It would be many years before the birth of the national park system, but Olmsted’s report laid the foundation. In 1916, Olmsted’s son helped draft legislation creating the national parks. Olmsted’s thinking in Yosemite also informed his later international campaign to preserve Niagara Falls.

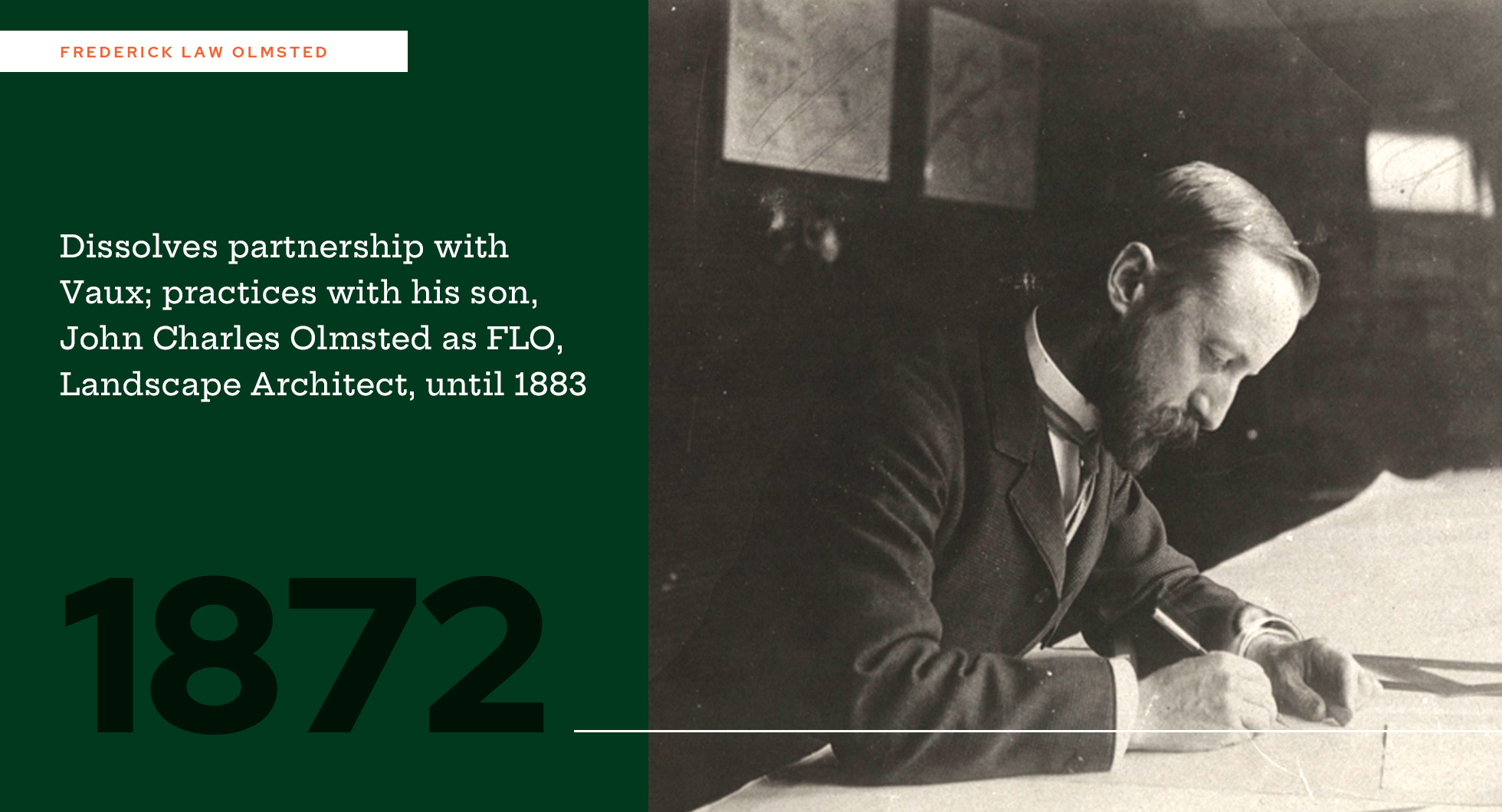

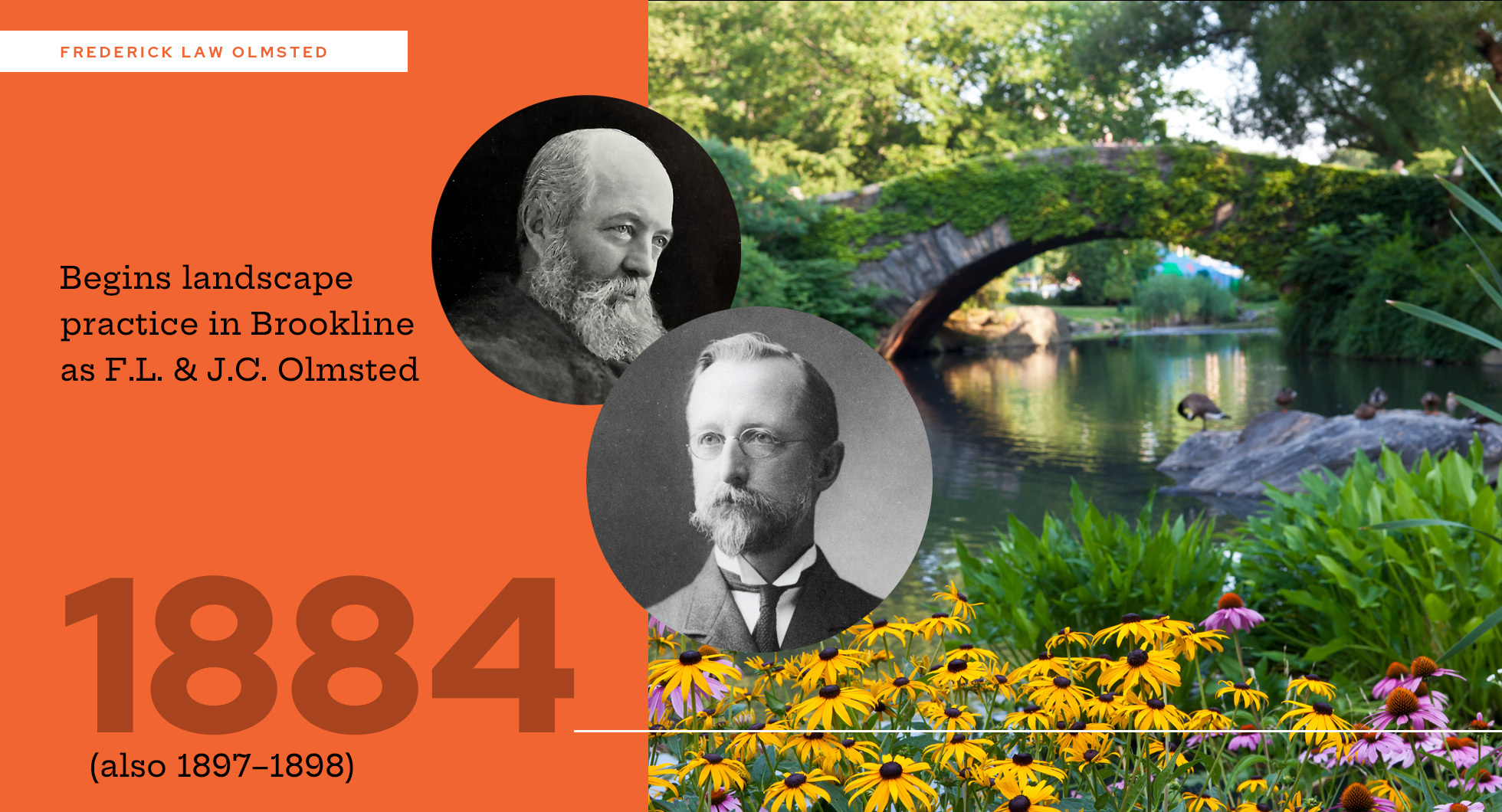

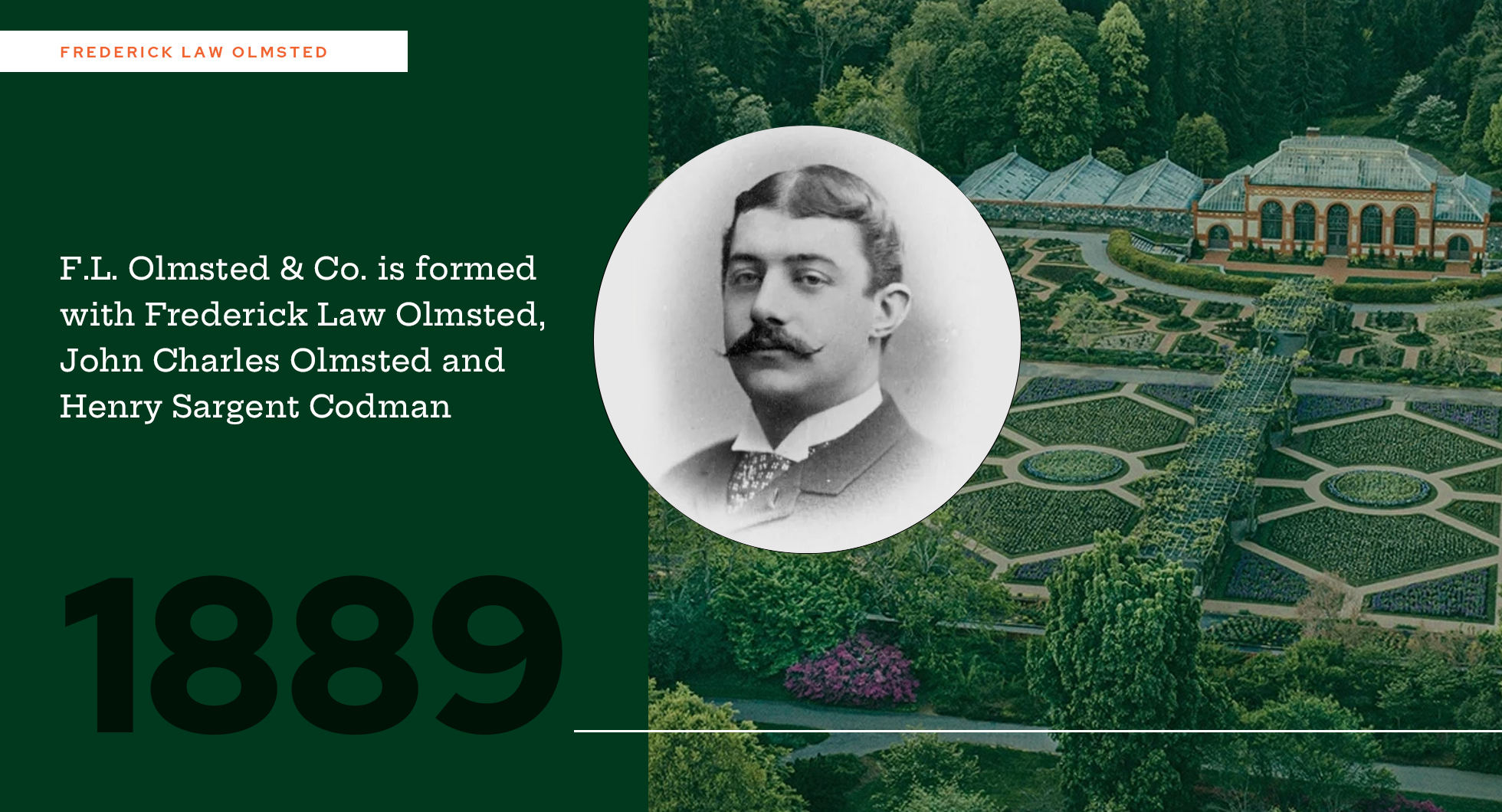

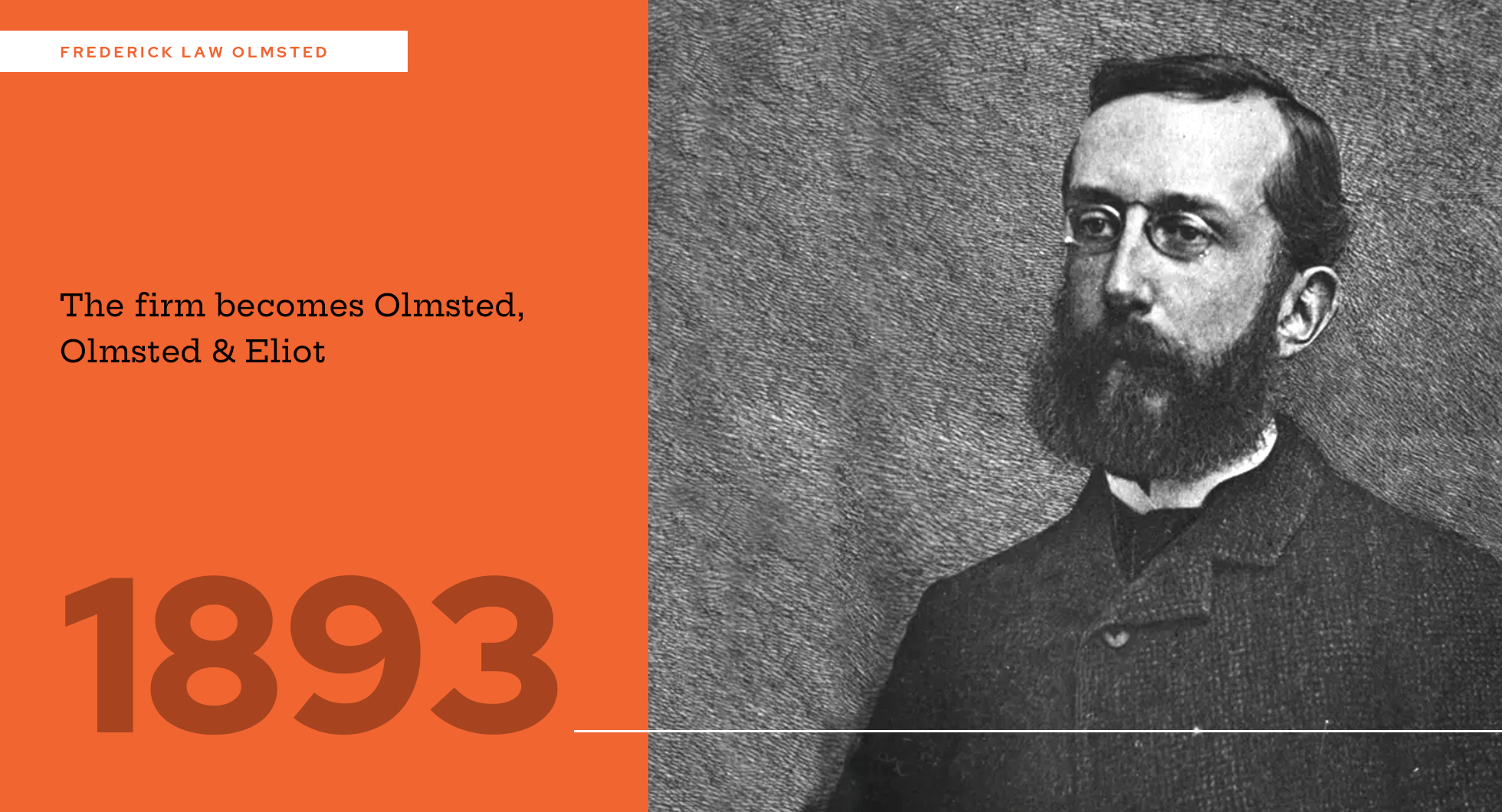

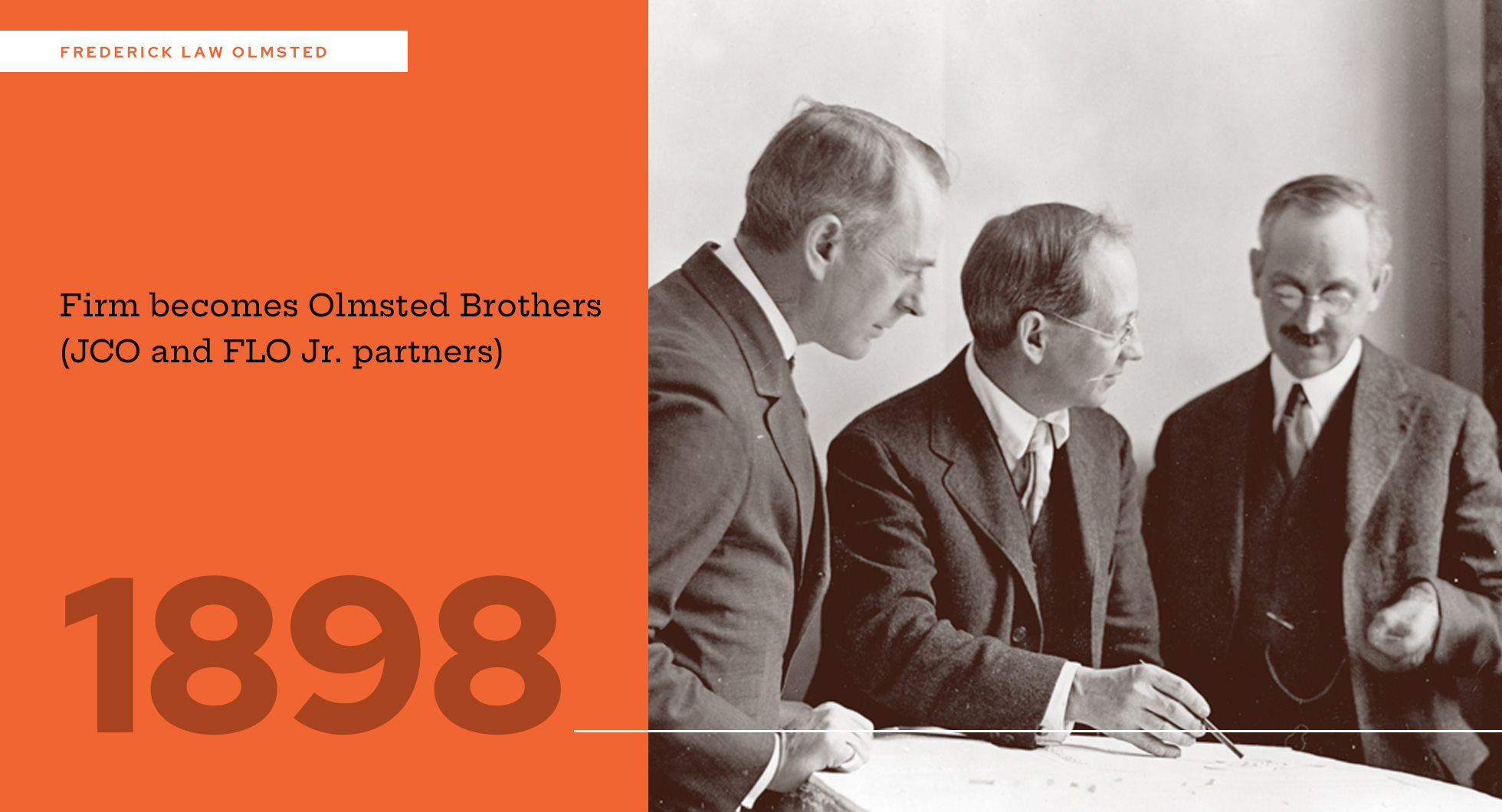

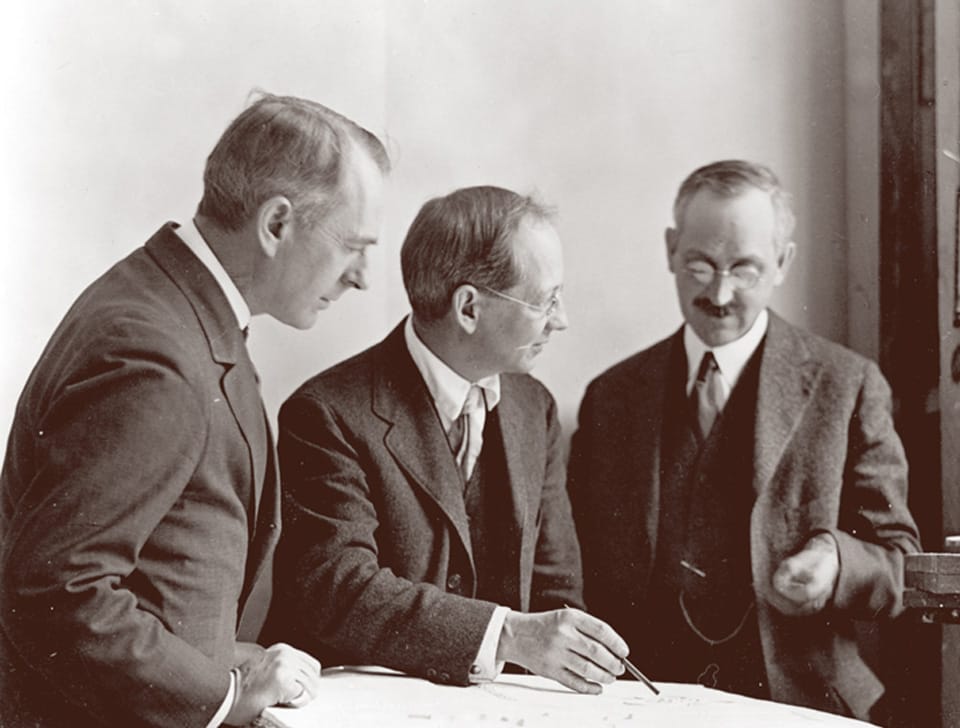

A New Generation of Olmsteds

Olmsted retired in 1895, but his sons, John Charles and Frederick Jr., carried on, and the Olmsted Firm was a functioning landscape practice for over 100 years with commissions for about 6,000 landscapes across North America. (Frederick Jr. was christened Henry Perkins and renamed by his father when he was about eight. He often dropped Jr. in his correspondence so it can be difficult to determine, on quick review, which Olmsted is writing.) The firm was almost singlehandedly responsible for developing the profession of landscape architecture and training generations of professionals, many of whom created their own firms, such as Charles Eliot, Warren Manning and William Lyman Phillips. John Charles was a founding member of the American Society of Landscape Architects and Frederick Jr. established Harvard’s Landscape Design Program. Today, the Landscape Architecture Foundation honors the Olmsted heritage by selecting annual Olmsted Scholars who are budding stars in the field. Fairsted, which served as both the home and workplace for Frederick Law Olmsted, is now a part of the National Park Service.

Read the story