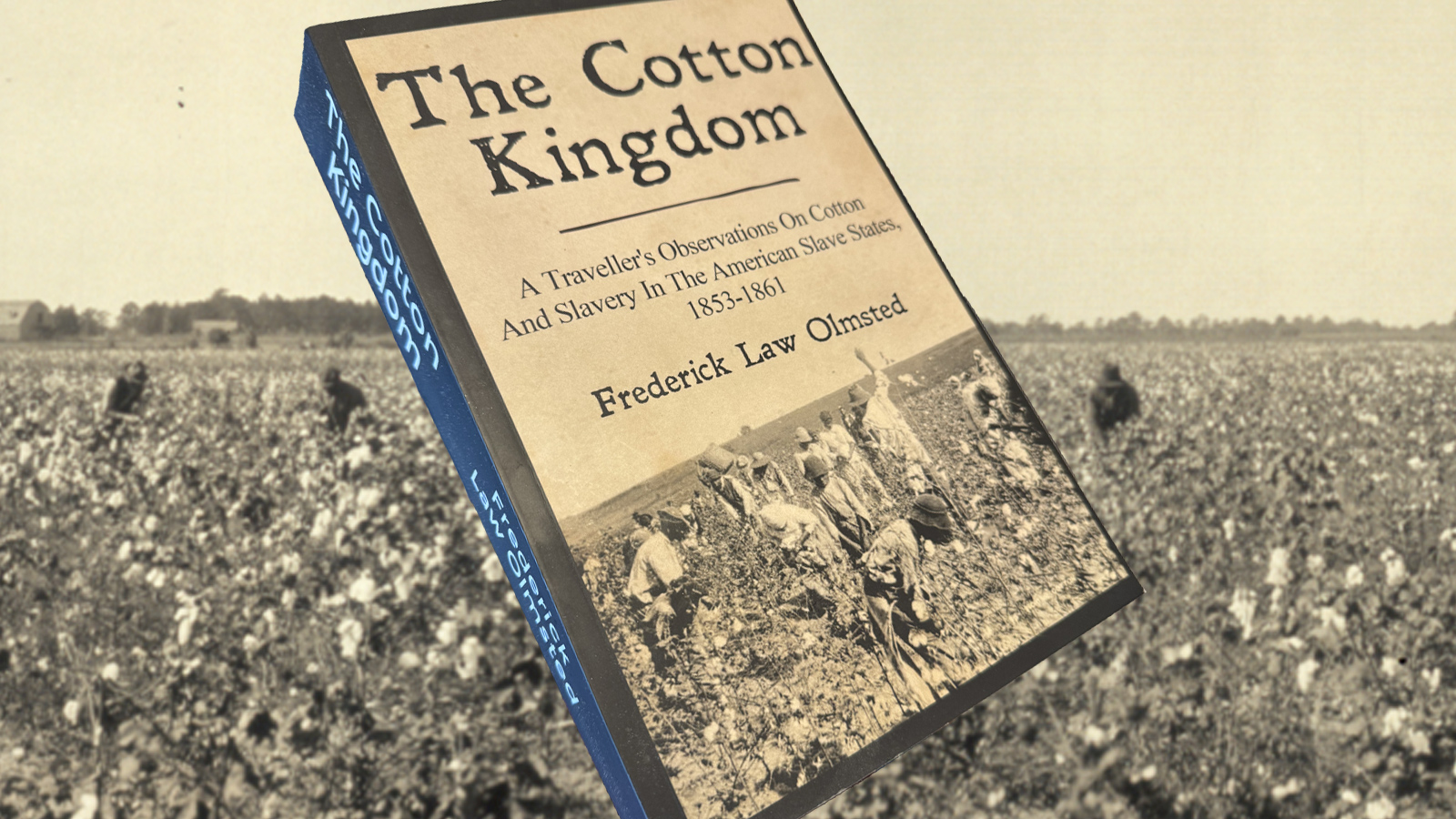

Olmsted’s account for The New York Times of the moral and economic shortcomings of slavery became one of the most widely read and cited sources before the Civil War. Scholar Charles Beveridge credits Cotton Kingdom, a condensed version of three books published in England in 1861, with “propaganda value” in undermining British notions of so-called Southern “aristocrats.” England’s decision to remain neutral during the War proved critical to the North’s ultimate success against the slaveholding South.

In its 1903 obituary, The Times noted that “Olmsted was not a militant Abolitionist, but that made his criticism of slave labor from the economical side all the more powerful. ‘A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, …’ appearing in New York in 1856, made a great sensation throughout the United States and England.”

Olmsted explored ways to ameliorate the lives of slaves, believing that education was an essential precondition to successful emancipation. According to Olmsted Papers Series Editor Charles Beveridge, Olmsted “saw social change as a slow process and believed that social reform could come about through an educational process that would change the habits as well as the beliefs of men.” Olmsted believed that the federal government had no authority to abolish slavery in the states, but that enlightened action by state governments and slaveholders was essential to bringing the end to slavery.

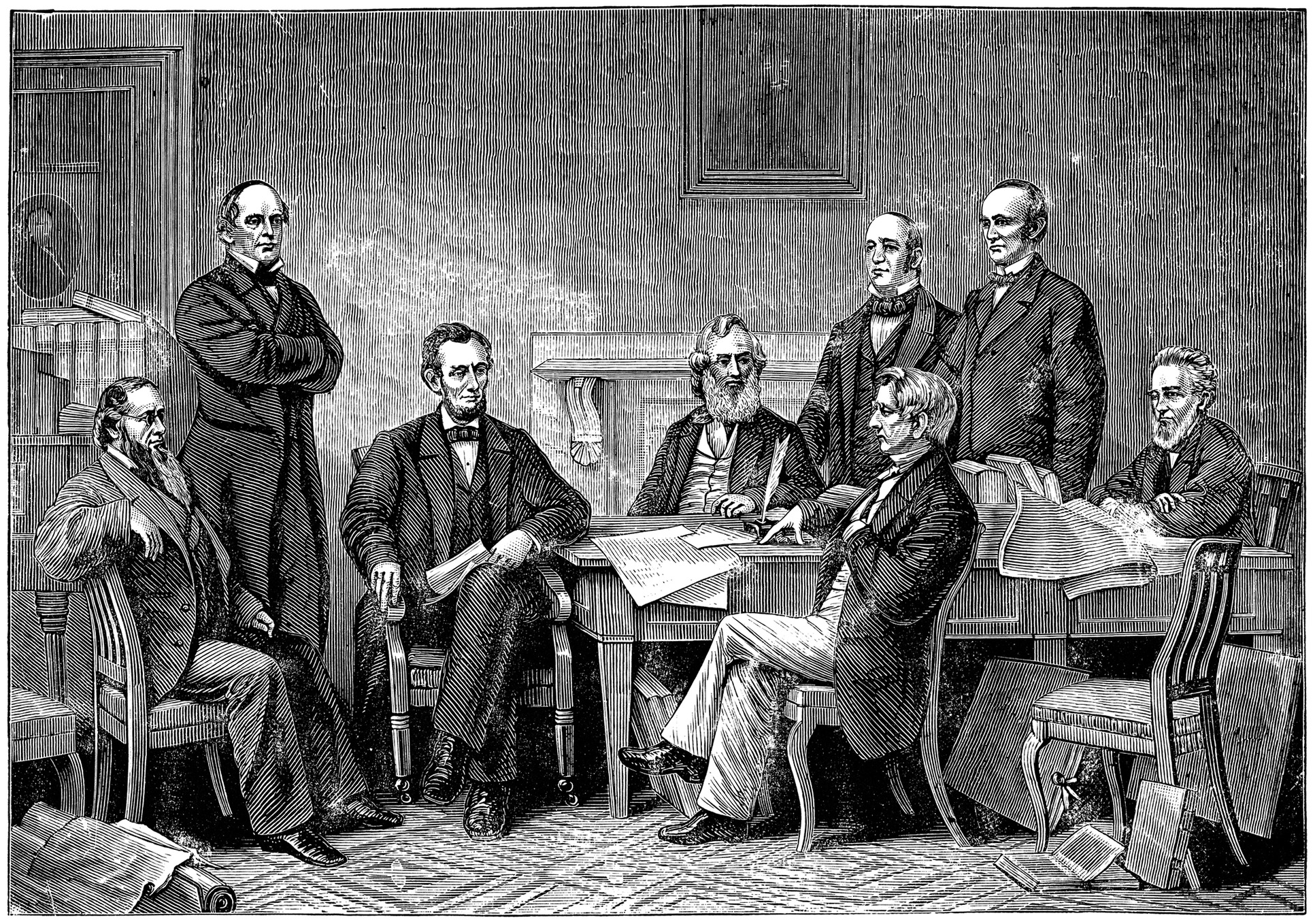

As the threat of slave state expansion increased, Olmsted’s thoughts became more radical and he turned to actions as well as words. In the late 1850s, Olmsted raised money and even acquired weapons for anti-slavery partisans in Kansas. He worked with local German residents and the New England Emigrant Aid Society to “build a barrier of free-soil colonies across Texas” to block the federal government from turning those lands into slaveholding states. In 1863, after the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, Olmsted testified before a special commission convened by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. There, he advised on integrating Black soldiers into the Union Army, calling for equal pay, respectful treatment, full arms and extra protections to ensure that Black prisoners of war were not re-enslaved. Scholar Rolf Diamant describes this testimony as just one indication of Olmsted’s prescient and enlightened understanding of the challenges faced by Blacks in the war effort. Alas, most of Olmsted’s recommendations were ignored.

Olmsted’s contributions to the anti-slavery movement were significant because Olmsted offered first-hand descriptions and a comprehensive assessment of the deplorable society slaveholding created. Many of his antislavery arguments consisted of moral condemnation and reports of violence and ill-treatment experienced by slaves. After traveling south, he provided an anti-slavery platform for the leaders of the newly forming Republican Party.

Thus, Olmsted was in the vanguard of efforts to end slavery and ensure the betterment of Blacks in the South – the most critical cause of his era. In his time, he was a leading anti-slavery activist who regularly battled the committed racists and defenders of slavery.