The year of 2022 celebrates the 200th anniversary of the birth of Frederick Law Olmsted, and 2023 will mark the 150th anniversary of the birth of a public park (kōen) in Japan. One hundred and fifty years ago, in 1873, when Central Park, the first public park in the U.S., was almost completed, park legislation was born in Japan with Cabinet (Dajōkan) Order No. 16. However, it was not until Hibiya Park, which opened 30 years later, that Western landscape design was introduced to Japanese public parks.

Hibiya Park was created as part of a modern urban planning project that called for a “new Western-style public park” with wide streets and a government office district, as befitting the imperial city of Tokyo. Surrounded by the Imperial Palace, business districts (Otemachi, Marunouchi, Yurakucho, Shimbashi, and Toranomon), a shopping district (Ginza), and a government office district (Kasumigaseki), the park has represented Tokyo and Japan as an urban park of historical and cultural importance for over 100 years.

From today’s perspective, Central Park and Hibiya Park seem to have much in common, such as being their respective nations’ first modern urban parks, located in the hearts of their respective cities, and diverse cultural centers. Nonetheless, the social backgrounds of the two parks are rather contrasting. This is because Central Park was conceived as a measure to improve the environment of a city that had deteriorated due to industrialization, while Hibiya Park was designed as a cultural device essential to a modern city. In other words, while the former was designed to resist the modern city by emphasizing the contemplation of nature, the latter was built with the enjoyment of Western culture in mind to complement Tokyo, the first modern city in Asia.

Is Hibiya Park, then, not regarded as Tokyo’s Central Park? This essay will examine the significance of Hibiya Park through a comparison with Central Park from three perspectives: history, design, and vision.

History: From the Birth of Modern Urban Public Parks to the Opening of Hibiya Park

The history of public parks in Japan begins in 1873, when the Western concept of “the public park” was introduced with Cabinet Order No. 16. In the same year, the first five parks were designated in Tokyo: Ueno Park, Asakusa Park, Fukagawa Park, Asukayama Park, and Shiba Park. Their locations were chiefly selected for economic reasons, such as low land acquisition costs, rather than from an urban planning perspective, such as public health, so it was nothing more than a forcible renaming of land within the precincts of an existing shrine or temple to “public park.” Hence, the spatial composition of the early public parks retained strong traces of traditional Japanese gardens.

The first public park created in conjunction with modern urban planning was Sakamotocho Park in Nihonbashi, which opened in 1889. It was the first to be realized among the 49 parks proposed in an urban rearrangement ordinance by the city of Tokyo in the same year. Although small in size, Sakamotocho Park was “modern” in the sense that it was established to improve public health in a dense urban area and to provide a playground to the adjacent elementary school, as well as shelter for local residents in mind, which sets it apart from the aforementioned first five parks. However, the design itself maintained the atmosphere of a garden created before the Meiji Restoration in 1868. At first glance, the lawn area gave an impression of “openness,” suggesting Western-style, but there were a small hill and a small arbor in the center of the lawn, the seven plants of spring were featured along the park’s paths, and conventional garden plants, such as Japanese pagoda trees, chinquapin, Japanese cypress, cherry, maple, and Japanese apricot trees, were planted on the lawn and around the perimeter that bordered the park.

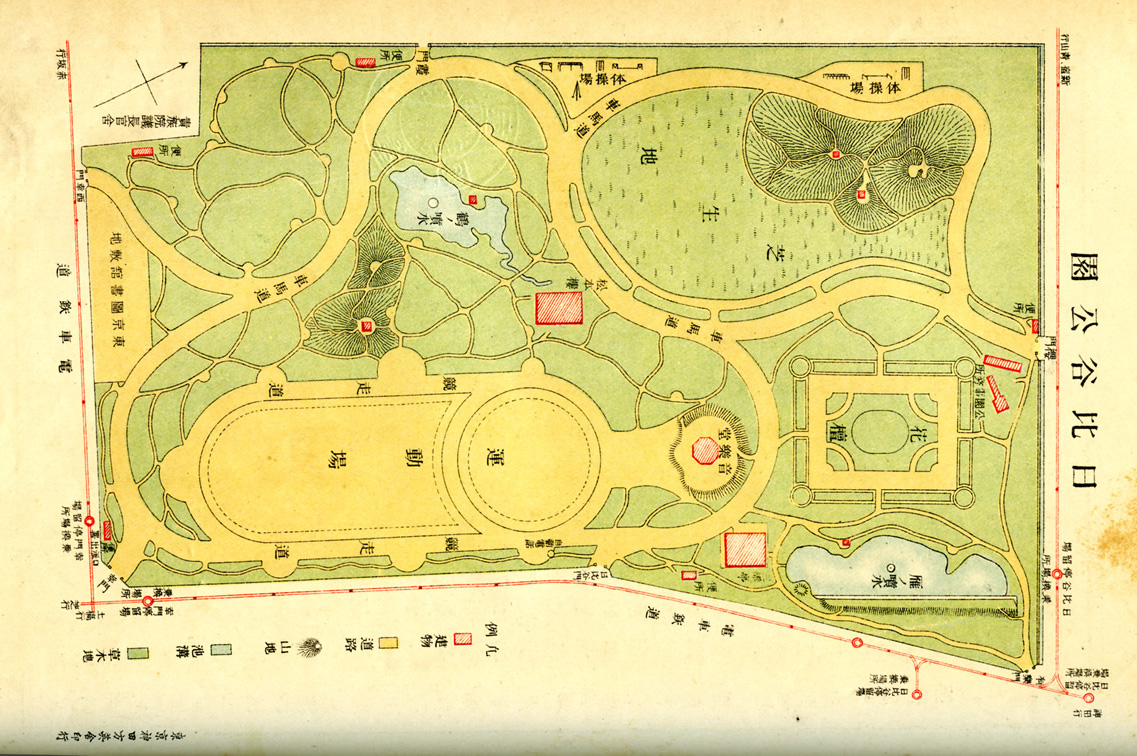

Contrary to the choice to initially develop Sakamotocho Park, it was Hibiya Park that the ordinance had proposed be developed first. After Hibiya Park was officially designated in 1893, a decade-long debate over its design ensued until the park opened in 1903. Experts representing various fields at the time, including gardener Yoshichika Kodaira (1845–1912), naturalist Yoshio Tanaka (1838–1916), and landscape architect Yasuhei Nagaoka (1842–1925), submitted a series of design proposals for Hibiya Park. Nevertheless, none of the designs was approved by the city council, which strongly insisted on a legitimate Western style, as they were all in the Japanese style, similar to the first parks that had been converted from shrines and temples. Architect Kingo Tatsuno (1854–1919), on the other hand, proposed a simple, formal park with an oval plaza in the center of the site and wooded areas around it, but neither did this convince the city council.

After many twists and turns, it was the forestry scholar Seiroku Honda (1866–1952) who was finally entrusted with the design of Hibiya Park. Honda is now known as the “father of public parks” in Japan, and his reputation is based on the fact that he was the designer of Hibiya Park. Actually, Honda’s specialty was not landscape architecture but forestry. According to Honda’s own recollection, he happened to see Tatsuno’s design for Hibiya Park and expressed his opinion to Tatsuno, who had been struggling with the project and compelled Honda to design the park.

Although commissioned to design the park by sheer chance, Honda seemed to have understood the essence of public landscaping. Scholar of landscape architecture Shinji Isoya explains that the essence means not the pursuit of individual expression or originality, as in the case of privately owned architecture and gardens, but rather an attitude of trying to find the best solution, while taking into account the different opinions of city council members, practitioners, and experts, as well as the needs of citizens. Indeed, Honda’s design clearly shows the care taken in many directions: he maintained the framework of the rejected proposals, while seeking advice from gardener Keijiro Ozawa (1842–1932) and horticulturist Hayato Fukuba (1856–1921) on the Japanese garden plot and flower planting, and furthermore consulted Gärtnerische Planzeichen (1891) by German landscape architect Max Bertram (1849–1914), so that the overall design was integrated with a graceful curved parkway, or carriage drive.

Design: Hibiya Park as a Place of Western Culture and Public Festivities

Honda’s design of Hibiya Park was the result of the synthesis of the views of experts representing various fields, such as horticulture, forestry, and garden design. In fact, soon after its opening, Hibiya Park became a model for municipal parks and a project that symbolized the dawn of landscape architecture (zōen) in Japan.

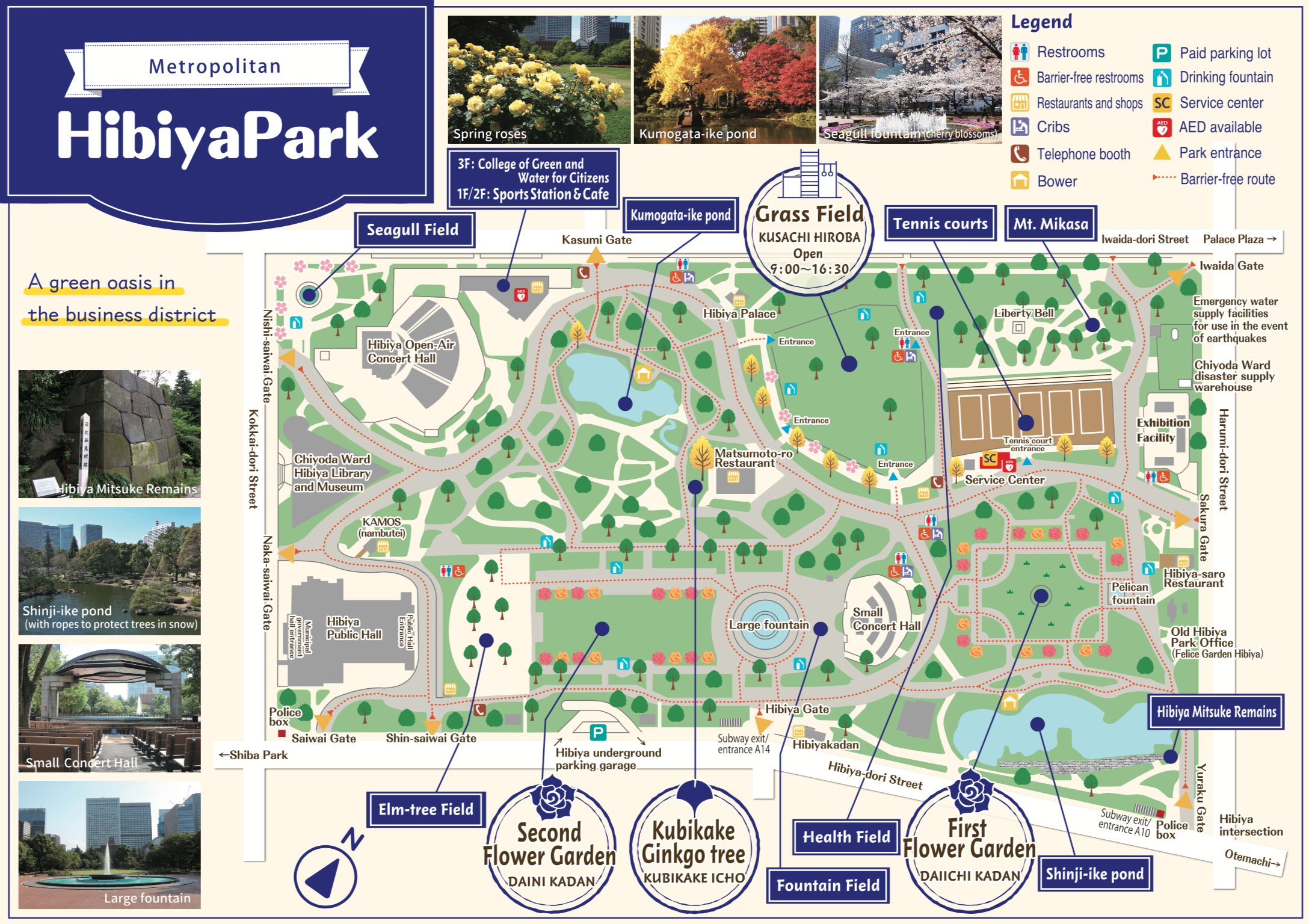

Hibiya Park is divided into four zones with different functions and characteristics by a large curving parkway. The northeast zone had a geometric configuration centered on a flower garden (now the First Flower Garden). To the east is a stone wall belonging to Hibiya Mitsuke (remains of the former Edo Castle), and a pond and fountain converted from the remains of the castle, which strongly remind us of the Edo era (1603–1867). The northwest zone was an idyllic open space consisting of a small hill (now Mount Mikasa) and a lawn (now the Grass Field). The southeast zone was an open area with a vast oval-shaped sports field (now the Second Flower Garden and Large Fountain) and a race track, and a music hall (now the Small Concert Hall) was established on the north side. The southwestern zone was a naturalistic wooded area with a German-style tree grove (now the Hibiya Open-Air Concert Hall), and an azalea mountain and grove of trees were created in the area between the sports field and the German-style tree grove.

Although some elements of Japanese gardens, such as ponds and artificial hills, could be seen in Hibiya Park, the park as a whole was certainly designed in a Western style. Moreover, Western-style flowers, food, and music were first introduced to the general public in Hibiya Park as symbols of Western-style culture, i.e. civilization and enlightenment. Many citizens admired the tulips and pansies, which were still rare at the time, in the flower garden, learned table manners at the Western-style restaurant, Matsumoto-ro, in the center of the park, and listened to a military band play in the music hall. Hibiya Park was a place where Japanese people encountered Western culture.

At first glance, the cultural character that characterized Hibiya Park may seem similar to that of Central Park. The reason being that, just as Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–1852), a landscape theorist who advocated the construction of a large public park in New York City, sought cultural and educational functions for the park, Central Park was already conditioned to incorporate various cultural elements, such as playgrounds, flower gardens, and a skating rink, when the design competition was held. In contrast, the Greensward plan by Olmsted and Calvert Vaux presented an image of the park that put emphasis on the contemplation of nature, while minimizing the use of buildings. In other words, while Hibiya Park aggressively embraced the culture of the “modern Western city,” Central Park embraced nature as its ideal antidote against the “modern industrial city.”

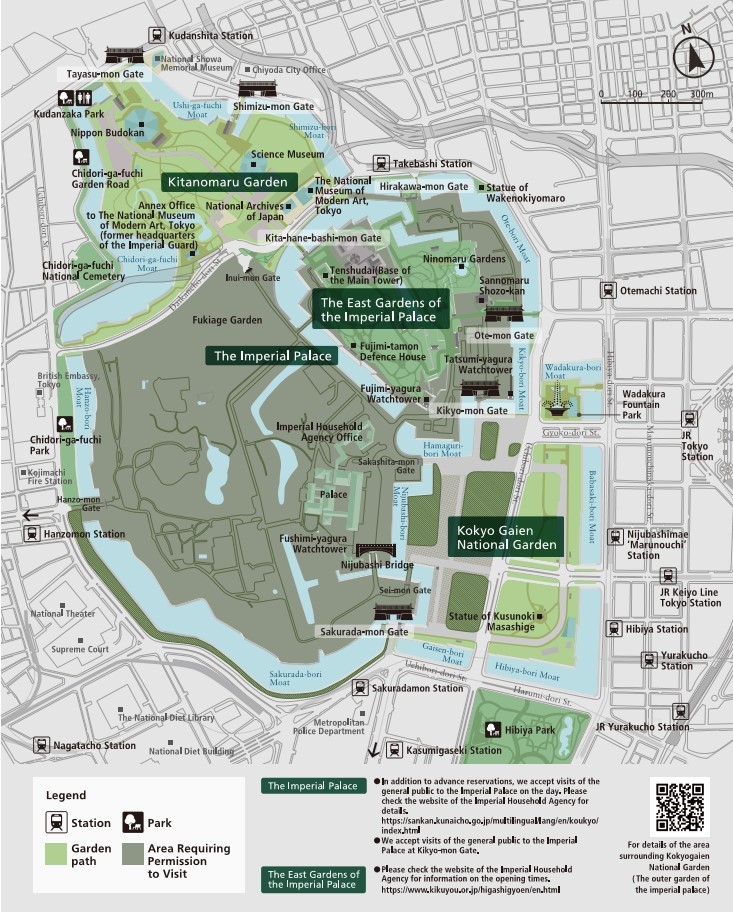

In addition, Hibiya Park was not only an epicenter of Western culture, but also a space for public festivities. Scholar of landscape architecture Ryohei Ono points out that Hibiya Park originally had a complementary relationship with the adjacent Kyujo-mae Plaza (now Kokyo Gaien National Garden). The Kyujo-mae Plaza was located in front of the Imperial Palace, and was a space for state ceremonies conducted by subjects in honor of the Emperor, and was developed in conjunction with the promulgation of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan in 1889. This spacious area, consisting of a wide, graveled road-like space and three rectangular lawn “round gardens,” was the site of large-scale events, such as the ceremony for the promulgation of the Constitution and celebrations for the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). In the same year that the construction of the Kyujo-mae Plaza was completed, it was decided that Hibiya Park would be developed on the site of the former military training camp just to the south across the moat and road. When Hibiya Park opened in 1903, it was used as a place for eating, drinking, and entertainment to complement the more formal events held at Kyujo-mae Plaza, such as hurrahing banzai, singing the national anthem of Japan, “Kimigayo” (“His Imperial Majesty’s Reign”), and welcoming a triumphal procession. It is thought that the relationship between Kyujo-mae Plaza and Hibiya Park was one between discipline and deviance complementing each other.

This dispersion of functions can also be found in Meiji Jingu Shrine, which is regarded as a landmark project in modern Japanese landscape architecture. The shrine consists of two precincts, the inner precinct and the outer precinct, and was constructed between 1915 and 1926. The inner precinct was designed as a sacred forest dedicated to the spirits of Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) and Empress Shoken (1849–1914), with a forest-like design that incorporated vegetation transitions, while the outer precinct was designed as a public park for people to train and relax, with a picture gallery and sports facilities to strengthen its cultural character. In 1920, the first parkway in Japan, Urasando, was planned as a connecting road between the inner and outer precincts of Meiji Jingu Shrine, and was realized in 1928. In Central Park, too, although within a single site, each section originally had a different purpose and function, and a corresponding landscape design was carefully adopted. For instance, the Mall and Bethesda Terrace area was designed as a promenade and plaza for wider citizens, the Children’s District as a playground for children, and the Ramble modeled on the Adirondack Mountains as a tourist attraction for the working class.

The dispersion of functions and design differentiation among multiple public parks and green spaces, as well as the formation of their interactive networks, provide important clues in helping us envision the future of Hibiya Park as Tokyo’s Central Park.

Vision: Towards Hibiya Park’s 130th Anniversary

In 2018, the Bureau of Construction of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government announced the Hibiya Park Grand Design for the park’s 130th anniversary in 2033. From the perspective of Tokyo citizens and visitors, issues regarding the park’s characteristics in terms of usage, of history and culture, and of location were discussed, and five visions were presented as follows:

(1) A high-quality park where everyone is welcomed and can spend time comfortably

(2) A park that works with the surrounding area to synergistically create new attractions

(3) A special park that expresses historical and cultural values

(4) A park that forms the core of a network of green and open spaces

(5) A park that is managed from the viewpoint of users in cooperation with various entities

Currently, a large-scale redevelopment project is underway around Hibiya Park. The Tokyo Cross Park Vision, jointly announced by 10 companies in April 2022, calls for the construction of the Imperial Hotel and three skyscraper towers on 6.5 hectares of land on the east side of Hibiya Park. In addition to the Imperial Hotel and three skyscraper towers, the plan calls for the construction of a 31-meter-high podium with an elevated green public realm and a 2-hectare-large plaza. The most striking features are to be two open-air “park bridges” that will overarch Hibiya-dori Avenue. By connecting the park with the commercial and entertainment district, currently separated by the avenue, via pedestrian decks, the plan aims to revitalize culture and the economy.

However, for Hibiya Park to truly become Tokyo’s Central Park, it is necessary to strengthen not only its cultural character but also its naturalistic character. Some have pointed out that the naturalistic character that Olmsted first envisioned for Central Park has been gradually weakened by the construction of children’s playgrounds and sports facilities over the past 150 years; the 341-hectare Central Park had enough land to accommodate a variety of cultural institutions, and the iconic landscapes of the Mall, the Sheep Meadow, and the Ramble have been preserved to this day. In contrast, Hibiya Park, with only 16.16 hectares, could not afford to host many facilities from the beginning. Nevertheless, large-scale cultural facilities (an open-air concert hall, a public hall, and library and museum) and sports facilities (tennis courts, a health square, etc.), which have been built on the German-style woodlands, Mount Mikasa, and the extensive lawn that has always existed within the confines of the park, have significantly reduced the park’s naturalistic character.

In order to solve this problem, the fourth vision of the Grand Design is worthy of attention. By reimagining Hibiya Park and the green spaces around the Imperial Palace as continuous and integrated, the naturalistic character of the park could be complemented. This idea itself is not new. As mentioned above, in the Meiji era (1868–1912), Hibiya Park and Kyujo-mae Plaza complemented each other in their roles as a space for public festivities and a space for state ceremonies, respectively. After World War II, Hibiya Park and the green spaces around the Imperial Palace— Kokyo Gaien National Garden, the East Gardens of the Imperial Palace, Kitanomaru Garden, Kudanzaka Park, Chidori-ga-fuchi National Cemetery, and Chidori-ga-fuchi Park— were collectively designated as “Tokyo toshi keikaku kōen daiichigō chūō kōen” (“Tokyo City Planning Park No. 1 Central Park”), and moreover, in the 2000s, Tokyo Central Park, a non-profit organization, advocated making better use of the network of greenery within this Central Park.

The total area of Tokyo’s Central Park is 156 hectares, about 10 times the size of Hibiya Park. If we were to include the National Diet Front Garden on the west side of Hibiya Park, and Shiba Park, the Former Shibarikyu Gardens, and the Hamarikyu Gardens on the south side, the total area would be 220.58 hectares, which is equivalent to about 65% of the area of New York’s Central Park. In addition, most of these parks and gardens, other than Hibiya Park, have relatively few cultural and sports facilities. Furthermore, they have a richly varied landscape, ranging from a feudal lord’s garden (daimyō teien) from the Edo era to a garden of deciduous trees (zōki no niwa) from the Showa era (1926–1989).

In considering the nature of such a network of public parks and green spaces, it is Brooklyn’s plans, including those for Prospect Park, rather than those for Central Park, that may serve as a reference. This is because, whereas Central Park is a naturalistic and cultural enclave within a single site, Brooklyn has a network of parks with different social functions and designs that complement each other. Olmsted proposed the Parkways in parallel with the design of Prospect Park, and worked on two more smaller parks: Fort Greene Park and Tompkins Park (now Herbert Von King Park). Prospect Park, the backbone of the project, adopted a naturalistic design similar to that of Central Park, while Fort Greene Park, where military ceremonies were held, adopted a more formal design, and Tompkins Park, a place of relaxation for neighborhood residents, was designed in a geometric style. Prospect Park has been able to maintain its naturalistic character over the years because other parks have allowed a wide range of public and private uses.

Similarly, in the city of Buffalo in northwestern New York State, there are three parks: the Park (now Delaware Park), for communing with nature; the Front (now Front Park), for official events, and with a magnificent view of the shore of Lake Erie; and the Parade (now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Park), located on a hill and for socializing; and the Parkways connecting them to create the park system. In short, Olmsted sees parks not as stand-alone entities, but as multiple entities in relation to various components of a city, such as public facilities, streets, and residences.

Therefore, if we are to envision a Central Park for Tokyo, we should not only improve Hibiya Park, but at the same time, we should reconstruct the park system, with Hibiya Park at its core and in an integrated manner. To this end, not only should physical access and circulation within the network be improved, particularly the connection between Hibiya Park and Kokyo Gaien National Garden, and the greening and walkability of Hibiya-dori Avenue, but also the purpose, function, and design of each park should be further clarified and differentiated in relation to the surrounding areas. In this way, Tokyo’s Central Park could reconnect its naturalistic and cultural character in various locations and promote a broader social program to accommodate the increasingly diverse attributes and needs of citizens.

Bibliography:

Imaizumi, Yoshiko, Meiji jingu: “Dentō” wo tsukutta dai purojekuto (Tokyo: Shinchosha, 2013). [今泉宜子『明治神宮――「伝統」を創った大プロジェクト』(新潮社、2013年)]

Ishikawa, Mikiko, Toshi to ryokuchi: Atarashii toshikankyō no sōzō ni mukete (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2001). [石川幹子『都市と緑地――新しい都市環境の創造に向けて』(岩波書店、2001年)]

Kuitert, Wybe, Japanese Gardens and Landscapes, 1650-1950 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017).

Ono, Ryohei, Kōen no tanjō (Tokyo: Yoshikawa kobunkan, 2003). [小野良平『公園の誕生』(吉川弘文館、2003年)]

Shinji, Isoya, Hibiya kōen: Hyakunen no kyōji ni manabu (Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing, 2011). [進士五十八『日比谷公園――100年の矜持に学ぶ』(鹿島出版会、2011年)]

Shirahata, Yozaburo, Kindai toshi kōenshi no kenkyū: Ōka no keifu (Kyoto: Shibunkaku, 1995). [白幡洋三郎『近代都市公園史の研究――欧化の系譜』(思文閣出版、1995年)]

Profile:

Ryosuke Kondo is an artist, landscape historian, and Adjunct Lecturer at the Graduate School of Global Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. With the support of the Tokyo Metropolitan Park Association, he is organizing a public lecture series and a symposium from September to December in 2022, to celebrate and promote Olmsted 200 in Japan.