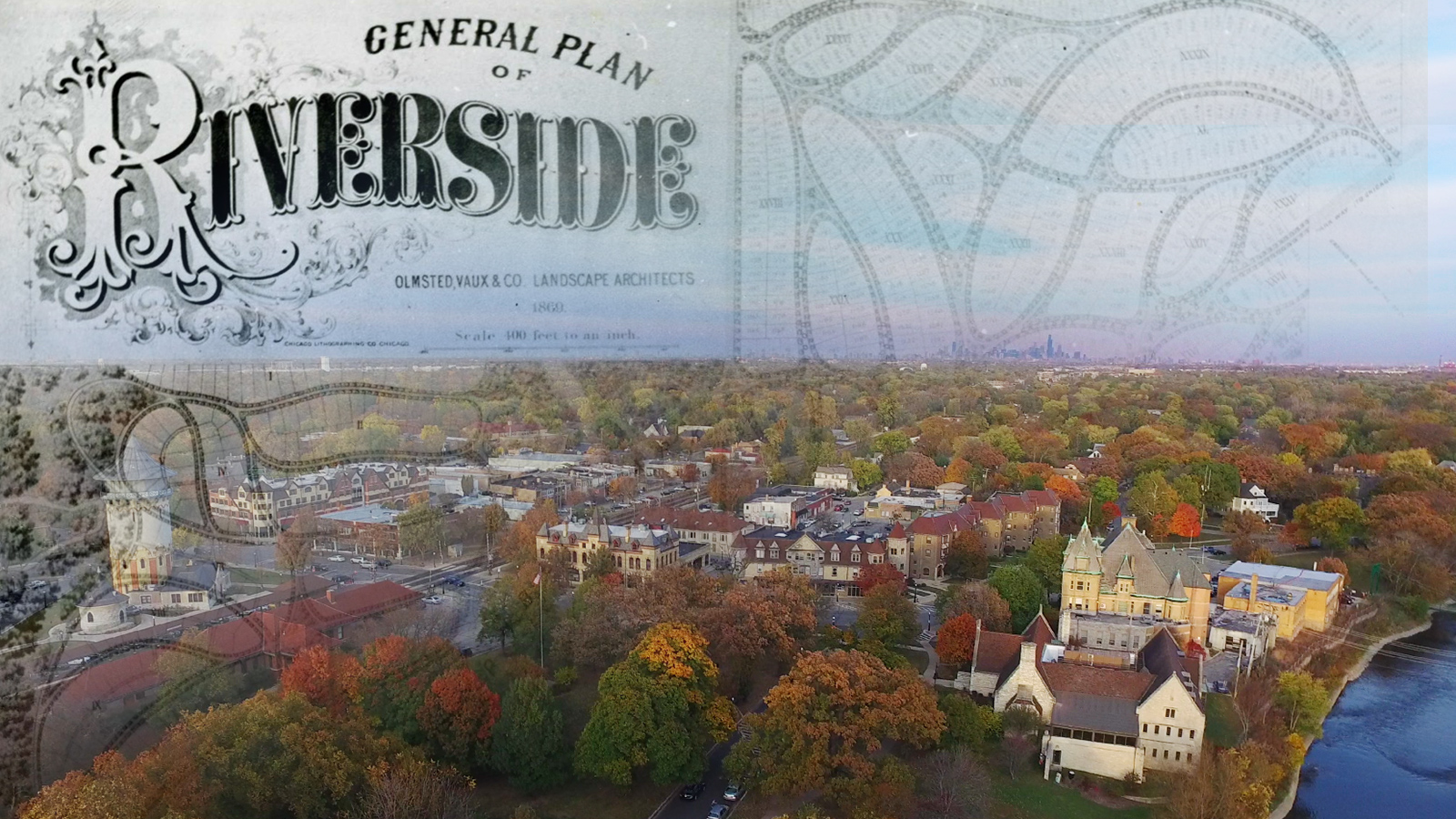

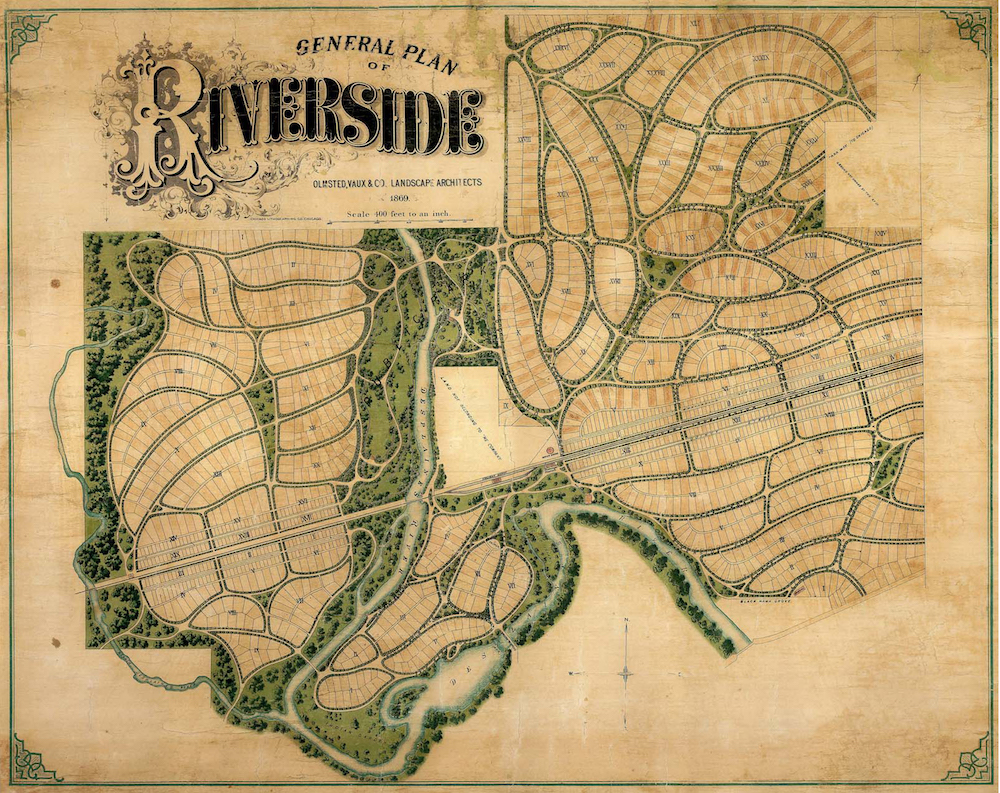

I was fortunate to be village president for Riverside, Illinois for eight years. Riverside is a National Historic Landscape District designed by Olmsted and Vaux in 1869. During my tenure as president, I governed according to two principles that I learned from Olmsted. First, that beauty is a civic necessity. Second, that the natural world, both in its raw state and as presented through landscape architecture, can touch the soul. Those two ideas— beauty and soul— were at the heart of how I governed as village president. For me, there was no policy so seemingly mundane that it did not have the potential to make Riverside more beautiful and thereby deepen and enhance its soul.

Olmsted is of course renowned for his landscape architecture, but his work has a profound psychological foundation that is less well-known. He believed that nature had an inherent power that could influence the human soul. Notably, he placed this power within nature, asserting that nature itself had psychological power. Olmsted was perhaps the first American ecopsychologist.

Olmsted’s work was specifically intended to be therapeutic. He made a direct connection between beauty and care of the soul (psyche-therapeia). Further, he believed that the restorative powers of natural beauty were critical for social reform and the democratic process. For Olmsted, beauty was a moral force for good. He believed that public parks and greenspace provided natural settings for citizens of all races and classes to interact. More importantly, he believed that nature and landscape architecture stimulated the free flow of imagination, thereby providing citizens a sense of what he called “enlarged freedom.”

These profound ideas are eminently practical, which Olmsted himself proved through his work. A major project we did in Riverside further makes this point. Our central business district was in dire need for attention. The old, exposed aggregate sidewalk was in its last days and the street generally had a dilapidated, somewhat neglected look. We set out, guided by an excellent landscape architect, to restore the district. The defining goal was beauty.

The final plan included a complete redesign of the street – sidewalks made from permeable pavers, raised planters constructed of native limestone and given organic, flowing curves (built to a height that would encourage people to sit on their edges and filled with native perennials), park-like benches that were situated at angles to one another to allow people to easily converse, beautiful lighted bollards that marked crosswalks of contrasting color with the newly-paved street, and bump-outs that added curvature while also protecting pedestrians.

The detail that changed everything was a meandering brick ribbon that wove its way down the sidewalks. Its river-like, wandering path within a path transformed the sidewalks. Although they were still straight, they no longer felt straight. Like the curvilinear streets that followed the geological contours of the land and invoked the Des Plaines River that gave Riverside its name, the ribbon imitated the way of nature. I like to think that Fred would have been pleased.

Benjamin Sells is a writer, psychotherapist, lawyer, and former village president of Riverside, Illinois. His book Beauty Matters: Civics Lessons from and Olmsted Village is available on Amazon here.