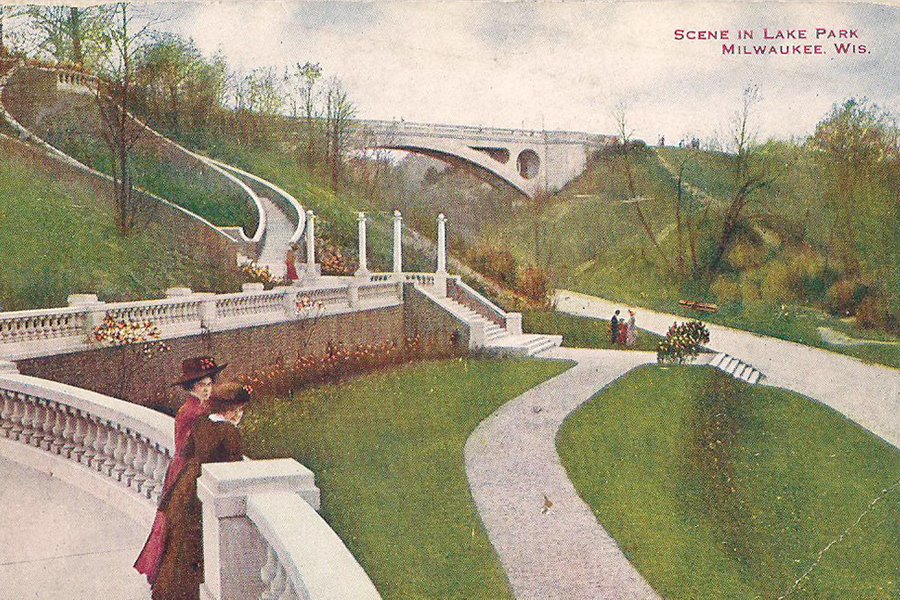

I left the quintessential Olmsted-shaped Louisville, Kentucky landscape two months ago for a public parks and outdoor leadership role in Chattanooga, Tennessee. In nearly every park-related discussion, I find myself unfailingly drawn back to the power of Olmsted’s landscapes. His life’s work, as experienced through the lens of built landscapes and public spaces, provides an incredibly rich and helpful vocabulary allowing diverse folks the capacity to explore together the moves (big and small) that are needed to create more livable, just, and healthy communities. I find this vocabulary revealed in responses I hear to the question below.

“Why do Olmsted’s ideas, landscape innovations, and design instincts matter today?”

Consider the following statement a provocation that I hope a graduate student one day will study. That being, thanks to the dedication and advocacy of the National Association for Olmsted Parks and dozens of specific Olmsted landscape-focused interest groups and public park advocates, Olmsted communities have an advantage in the space of city-shaping efforts not available to folks in communities that lack these legacy public spaces. This is because it is in our Olmsted-informed cities that leaders have privileged access to a vocabulary of public park space function and design, an awareness and appreciation of the scale of work required to create lasting landscapes, and an understanding (or at least shared experience of) the fragility of these places.

Uttering the word “Olmsted” in Buffalo, Rochester, DC, or other city with his works carries seriousness of purpose and intent. When leaders align their interests/cause/vision with Olmsted in those places, the conversation elevates. Folks are no longer talking about simply trees, playgrounds, and ballfields. The community is now talking about something far richer and more important. Colleagues might say the same for the work of Kessler in Indianapolis, Cincinnati, and Kansas City, and John Nolen in Venice (Florida), Madison, and Roanoke.

The point remains the same, the best city-shaping work requires a serious (and optimistic) intent for the outcome. Our best cities— including the ones yet to be built— will be special because they build on the power of public parks and landscapes as foundational “must have’s” from the starting block. Olmsted’s legacy is a gift to think and work in this space defined best by Laurie Olin when he catalogued Olmsted’s work as being done “at the scale of the problem.”

So, in the 21st Century, how do we make Olmsted’s lessons matter today?

I’m neither an architect, historian, ecologist, or planner. I simply love parks, particularly urban parks. It’s the juxtaposition of these spaces in urban settings that sets my imagination running. I feel more connected to a city when I walk through an intact Olmsted landscape. May I suggest here that the prime lesson of Olmsted’s landscapes isn’t one necessarily of design. Rather, perhaps the biggest lesson lies in the capacity Olmsted uncovered within himself to envision, create, and sustain beauty in the face of remarkable contradictions. Amid massive urbanization, immigration, social turmoil, economic booms and busts, and a consumptive spirit that had a nation exploiting every known resource with little consideration being given to the future, Olmsted created places of beauty, harmony, and timelessness.

Throughout the last years before he left us, author Barry Lopez gave several interviews that became podcasts. It was during these interviews that a consistent theme emerged from this most esteemed and thoughtful observer of nature and the human condition. He kept coming back to living with contradiction as being the defining characteristic of the next century.

How will we live in the face of unrelenting and accelerating impacts of climate change, many of which will be felt most in metro areas, particularly in the developing south? How do we build glittering, city-shaping and beautiful urban landscapes in places where people are increasingly separating themselves from nature quite intentionally? How do we sustain parks that are cycling through long-term maintenance needs and landscape succession while also creating and building new parks to serve our cities on their growing edges? And will we advance the absolute centrality of great design in our work when people will say that we should instead direct finite resources to solve very real and finite challenges such as food insecurity, unaffordable housing, and increasing economic and social isolation?

Reflecting on Olmsted’s work in his moment(s) from the 1800’s dealing with contradictions of that era, I find the courage, confidence, and vision that will be necessary for our cities in the coming decades. The challenges above are very real. In the face of this reality, it will be the responsibility of leaders to create, sustain, and embellish rare urban green spaces to provide hope to millions who otherwise might not have any reason to hang in there. If joy and peace are to be found in cities, people will have to make this happen.

Our work in cities today parallels the work Olmsted effected in the 1800’s. He gave hope for tomorrow by doing the work of his day. We should aspire to do the same. In doing so, we are honest about the challenges being faced, and respond with optimism and hopeful interventions that do make life better. Olmsted himself was challenged in this space emotionally and psychologically. He carried the pain. We should expect to do the same. And that is perfectly OK. Olmsted’s vocabulary of planting young trees, establishing sight lines to far away horizon lines tells us that we can act big. And big will stick around if we insist on it.

And the way to find the courage to get to the big park moves of today is found by looking at Olmsted’s works today— I’m always a fan of showing the greatest achievements as the point to what is possible— but we don’t stop there. Rather, we take our allies on a journey alongside Mr. Olmsted. We show the pain he faced. We show the turmoil he sought to address. We remind everyone of the difficult contradictions he wrestled with while creating the greatest of our nation’s public spaces.

Olmsted created beauty in the face of some very dark days. We will be asked to do the same. We should acknowledge this, then lean into it. And we should be thankful that a Rosetta Stone to build the community vocabulary necessary to meet this challenge has been left for us scattered across the nation in some of our most precious public landscapes. That’s a legacy we should attach to, add to, and celebrate. We should build parks. Big parks. More parks. Doing this is the only way we can help cities be humble and welcoming spaces for people living amid massive contradictions.